A network that labels Sikh activists as “extremists” and attempts to undermine calls for Sikh independence has reappeared on social media – despite platform takedowns in November 2021. CIR reveals the tell-tale signs of coordination, despite the network’s concerted efforts to appear credible and authentic.

This research uncovers a network of fake accounts on social media pretending to be Sikhs in order to undermine Sikh activists, stoke cultural tensions and promote Indian government narratives. These accounts label Sikh activists as “extremists”, and label themselves as “real Sikhs”.

The influence operation consists of profiles using the same identity across Facebook, Instagram and X (formerly Twitter). Accounts use images of real people, many of whom are Punjabi celebrities, and post the same content across platforms. The use of manipulated images, memes and videos, and descriptive, lengthy hashtags are common in their posts.

The network shares traits with another significant network identified by CIR in November 2021. At the time, that network was reported to social media platforms, which led to the suspension of all of the reported accounts. However, the majority of accounts identified in this network were created during or after December 2021 and have been prolific in their posting since creation. This indicates that despite platform actions to remove the accounts, the actors behind the campaign have created new accounts to continue the operation.

The network identified in this research consists of at least 53 identities and more than 100 accounts across platforms. These accounts attempted to bolster their credibility by using believable Sikh names, having profile and cover photos, and boasting a supporter network of between 1000-10,000 followers each, indicating a significant effort to appear authentic.

The posts and images shared by the accounts suggest that the network aims to undermine Sikh activists and the Sikh independence movement. It does this through the trolling of Sikh activists such as Gurpatwant Singh Pannun – who was the target of a foiled assassination plot in 2023 – and by labelling notions of Sikh independence as extremist.

Campaigns targeting Sikh independence

The network uncovered in this research promotes narratives labelling calls for Sikh independence as extremist. This independence movement is often referred to as the “Khalistan” movement, which refers to a campaign calling for the creation of a sovereign Sikh state (called Khalistan) in Punjab, India.

The silencing, undermining and targeting of those who promote Sikh independence has been a recurring issue impacting communities within India, and internationally.

The content produced by the fake network covers a wide range of narratives to target Khalistan activism, including:

Claims such as the Khalistani movement is a terrorist group undermining India

Claims Khalistan is sponsored by Pakistan

Claims related to Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom harbouring “Khalistani terrorists”

Undermining noteworthy politicised events in India, such as the farmer protests

Trolling Sikh activists, the most prominent of which was Pannun

Figure 1: An example of content posted by “Jasleen Kaur”, one of the accounts in the network. These two tweets were the most viewed and amplified posts on X made by that account.

The political backdrop

Militant Khalistan separatists waged a “violent insurgency” in India throughout the 1970s and ‘80s. Thousands of people were killed. Today, a small number of groups still exist in India that call for a Khalistan “homeland”, such as the Khalistan Liberation Force – an organisation banned by India.

Such groups make up a small proportion of modern Punjabi politics, and pro-independence politicians are rare. However, there is still some backing for Khalistan independence among the Sikh diaspora and growing support for jailed separatist leader Amritpal Singh. Despite limited support for the movement and little evidence of militant activity since the 1990s, the Indian authorities appear determined to clamp down on activists.

Information operations waged against critics of India’s policies and designed to subversively promote Indian government narratives have been identified in the past. For example, operations have targeted the EU and UN, attempting to manipulate voters, influence public perception in favour of the government, amplify violence against protesting farmers and troll Modi Government critics.

Journalists have been key targets of India’s information campaigns. Examples include the trolling of women journalists such as Rana Ayyub, as well as those who have interviewed Sikh activists.

Attempts to silence critics have not just been waged online through trolling campaigns and death threats, but have also been waged offline. In April 2024, the US Department of Justice announced charges in connection to a foiled plot directed by an Indian Government employee to assassinate US-based Sikh activist Gurpatwant Singh Pannun. That report also indicated that there may be more India Government critics that have been or will be targeted, potentially including a Sikh activist who was murdered in Canada in June 2023.

With the increasing threat to journalists, activists and critics, both in India and abroad, India ranks 159 out of 180 according to the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index 2024.

Crossover with the farmers’ protests

The network uncovered in this research builds off the back of a network CIR previously identified in a study of the online environment during the farmers’ protests in India which have been ongoing since late 2020.

Analysis of the past network revealed coordinated attempts to delegitimise the farmers’ protests, alleging they had been “hijacked by Khalistani terrorists”. The network in this report appears to be an extension of the previously identified network and has increased messaging to label Sikh independence as extremist during continued farmer protests in 2024.

The farmers’ protests began in response to legislation passed by the Indian Government in 2020. Many farmers involved in the protests come from India’s Punjab region.

In November 2021, the Indian Government announced the repeal of the laws amidst mounting pressure and scrutiny. The laws were contested by farmers’ unions claiming they were “anti-farmer” as the laws put farmers “in danger of becoming captive to companies” and that farmers would be left worse off.

Indian media claimed the farmers’ protests were hijacked and infiltrated by “extremist” groups, fuelled by claims from Indian politicians that there were links between the farmers and the pro-independence Khalistan movement. Some farmers claimed the statements about extremism were “government propaganda” to delegitimise the movement, label farmers as terrorists, and scare people into supporting the government’s crackdown on the demonstrations.

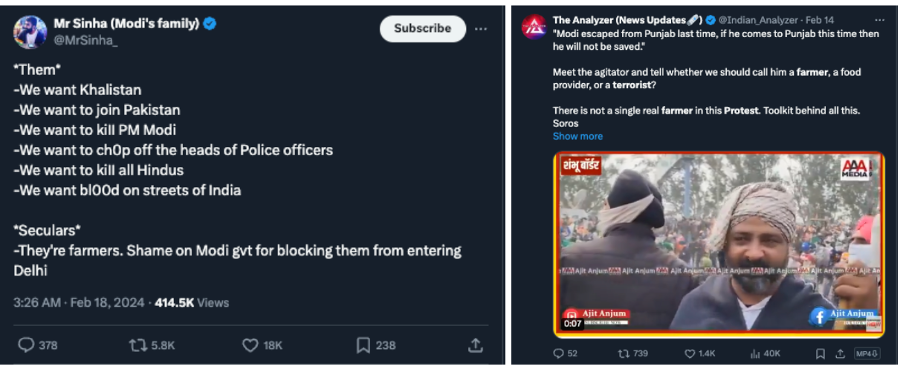

Farmers protested again in February 2024, demanding minimum crop prices. Police used tear gas on the protestors and fired plastic bullets into crowds. Human Rights Watch reported on the interference with the farmers’ right to peaceful protest. Narratives were again broadcast online including claims that protestors were extremists, while others claimed there were no farmers in the protest.

Figure 2: An example of widely shared content posted during the farmers’ protests in February 2024, by political commentator and Modi supporter “MrSinha_” and social media “news” account “The Analyzer”.

Network tactics and identifiers

The network of accounts studied in this research attracted scrutiny due to a number of indicators, such as their appearance, content and the way they deployed narratives. This section of the report will detail how the accounts were made, and then how the accounts posted their content.

Analysing how the accounts posted content and how they were created reveals a pattern of coordination. This research shows uniformity across the accounts, including the same creation dates, posting times, images shared and keywords used.

How the accounts were made

The accounts in this network bore characteristics that indicate they were part of a coordinated campaign designed for a specific purpose: to appear as Sikhs with believable profiles across platforms, using real photos as profile pictures and having significant follower numbers. This authentic appearance enabled the accounts to avoid detection as spam or fake accounts.

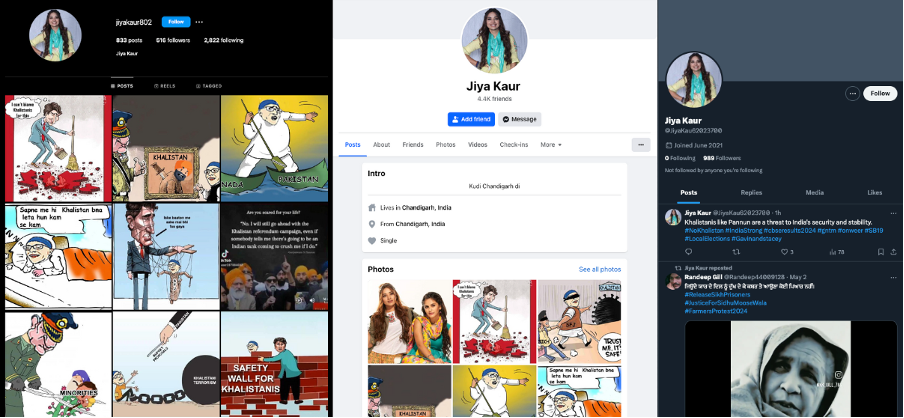

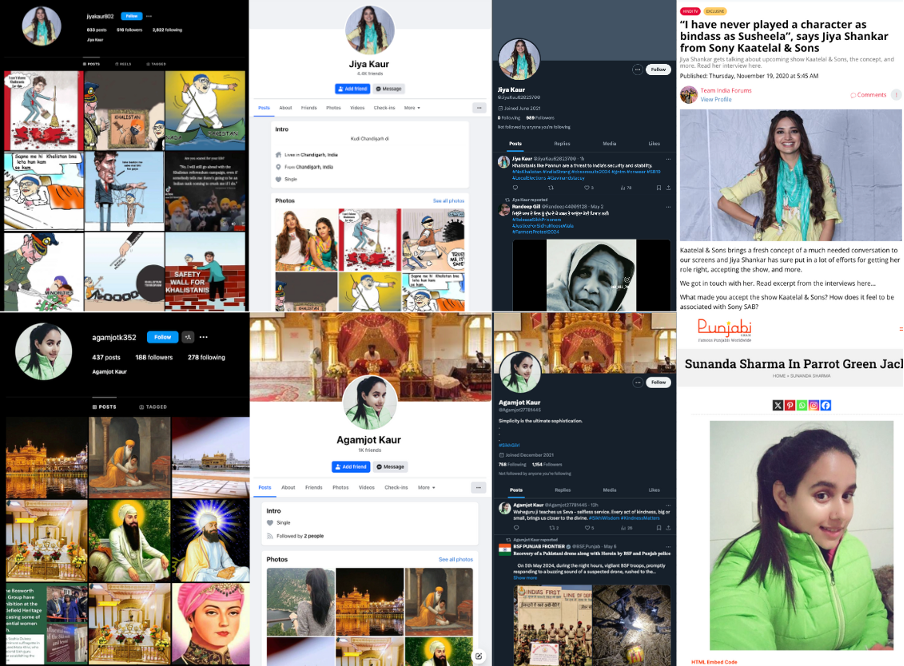

Figure 3: Screenshots of profile “Jiya Kaur” from left to right: Instagram, Facebook and X.

The account depicted in Figure 3, Jiya Kaur (@JiyaKau62023700), is one example of the many accounts identified in the network. The accounts use the same photo and name across platforms, indicating an attempt to create an online personality. In Figure 4, clear duplicates of the profile were spotted on Facebook and X. A number of the accounts also had profiles on Instagram.

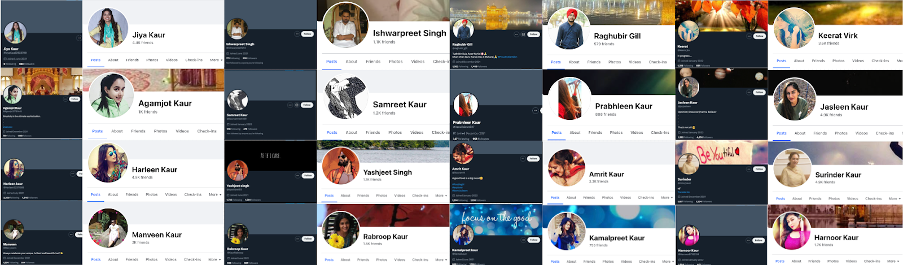

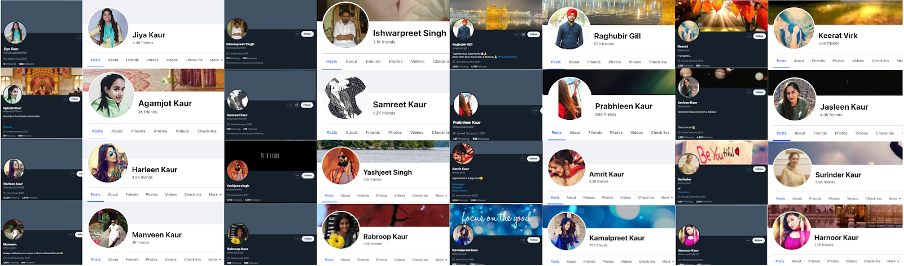

Figure 4: Screenshots of a sample of the profiles identified in the network and how they are seen copied in appearance on X and Facebook.

Similar to the campaign identified in November 2021, the accounts use profile pictures that are traceable to Indian celebrities. In Figure 5, the accounts Jiya Kaur (@JiyaKau62023700) and Agamjot Kaur (@Agamjot27781445) can be seen using images of Indian actress Jiya Shankar and singer Sunanda Sharma.

Figure 5: Screenshots of the Instagram, Facebook and X profiles of the accounts “Jiya Kaur” and “Agamjot Kaur” and screenshots of the websites where the profile images originated from.

Out of the 53 profiles analysed in the research, 26 of them appeared as female with the surname “Kaur”. Kaur is a surname primarily used in the Punjab region, indicating an intention to appeal or resonate with Sikh audiences. This was also the case with the past network that primarily used female-appearing profiles with the same surname.

This research also found that the majority of the accounts were created in December 2021 and January 2022. These creation dates are possibly linked to our past reporting in November 2021 of a prior version of the network, which was suspended for violation of rules prohibiting platform manipulation and fake accounts on X and inauthentic behaviour policies on Meta.

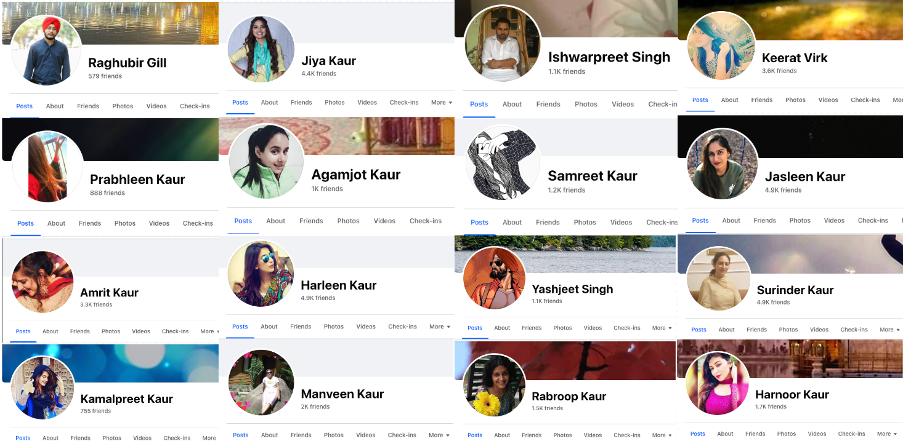

Accounts in the network also had relatively large follower numbers. Many of the accounts on Facebook were seen with between 1000-4000 friends, as seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Screenshots of a sample of the accounts in the network that were on Facebook.

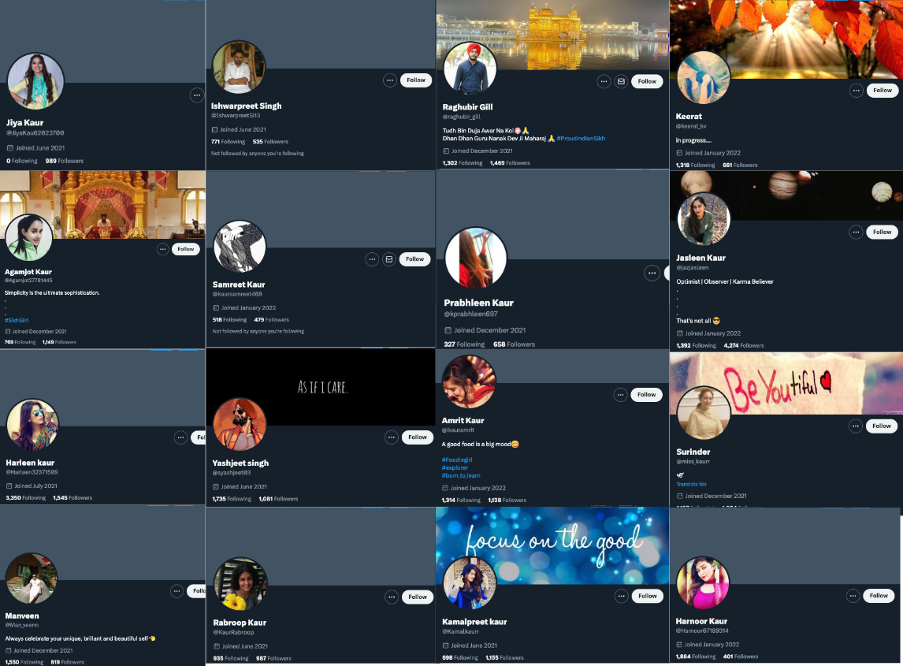

Similarly, on X, many of the accounts had follower numbers ranging from 300-2000 as seen in Figure 7. These friend and follower numbers are not typical of accounts in information operations designed to spam hashtags and narratives, and indicate an attempt to build a more believable online persona.

Figure 7: Screenshots of a sample of the accounts in the network that were on X.

How the accounts posted content

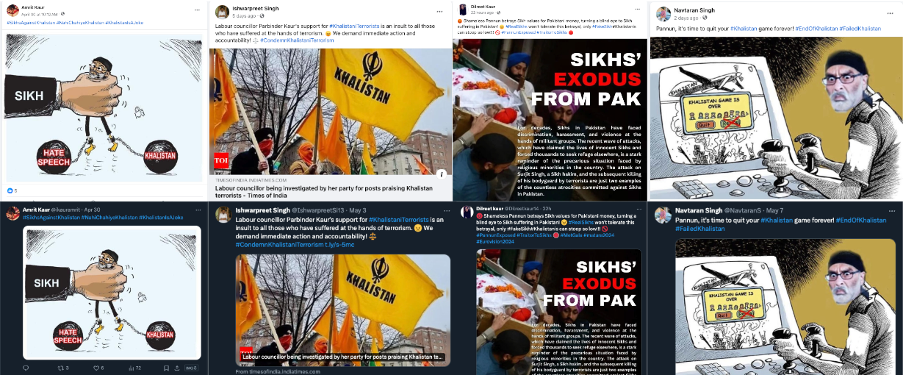

The profiles in the network posted very similar content, often overlapping in images, memes and keywords. One of the common factors between many of the accounts was the use of hashtags referencing Khalistan and terrorism. This can be seen in the figure below, showing how the accounts cross-posted the same text, tags and images across Facebook and X.

Figure 8: Screenshots of a sample of the content posted by accounts in the network on Facebook (top) and X (bottom).

Post times

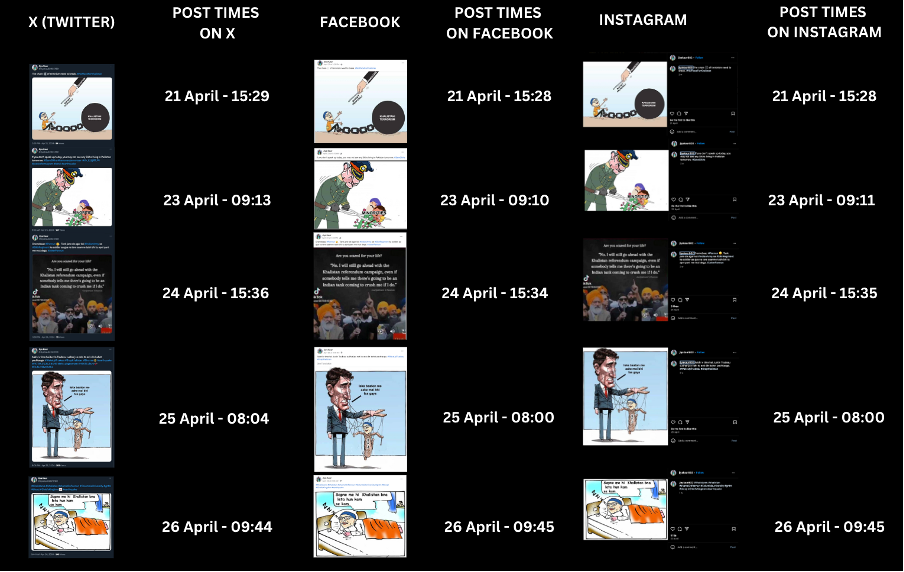

Our research analysed the times that each post was made by profiles across platforms. The posting times indicate that many of the accounts within the network post the same content seconds or minutes after the other. This behaviour is common practice for fake profiles operated by a human user. The user will have a set text and image they want to share and will log into each account one at a time and manually post the content.

As an indication of how the accounts in the network post across platforms, in Figure 9, the posting times can be seen from account “Jiya Kaur” (@JiyaKau62023700) between 21 April and 26 April 2024. These times indicate the practice taken to make daily posts from the same profile across platforms.

Figure 9: Screenshots of a sample of the content posted by the account “Jiya Kaur” on X, Facebook and Instagram, and the corresponding post times of each piece of the same content.

Signs of automation

In looking at how the network’s accounts posted information, there were some signs that tools may have been used to help automate some of the stages of posting content across the platforms. These include post times, spelling mistakes repeated across platforms and high volumes of comments in a short window of time.

There were signs of automation, or at least attempts to use tools to automate the posting of content on X. This is evident in some of the posts from accounts in the network.

Figure 10 shows a post by an account named “Paramdeep Ahuja” (@AhujaPamm), under which comments from other accounts in the network are visible. The comments use numerous emojis and words that appear to have been part of an automated posting pattern. Those comments were made by the accounts in a window of a few minutes.

Figure 10: Screenshots of a post (left) from one of the accounts in the network, and (right) comments posted underneath by other accounts also from the network.

Similarly, the post by “Jiya Kaur” (@JiyaKau62023700) in Figure 11 also shows the same pattern of behaviour from the accounts, indicative of auto-posting emojis and words. All of the comments made by “Jiya Kaur” in the post were made in a window of six minutes.

Figure 11: Screenshots of a post (left) from one of the accounts in the network, and (right) comments posted by other accounts also from the network under that post.

In some cases, accounts copied text across platforms, consistently making spelling mistakes in hashtags despite regularly using them. For example, in Figure 12, the account “Karanveer Singh” (@Karanve50449212) can be seen posting with spelling errors in the hashtags #NeverForgetKhalistaniTerrorism and #RealSikhs.

Figure 12: Screenshots of posts including mistakes in hashtags, copied across X (left) and Facebook (right).

Fake and manipulated images

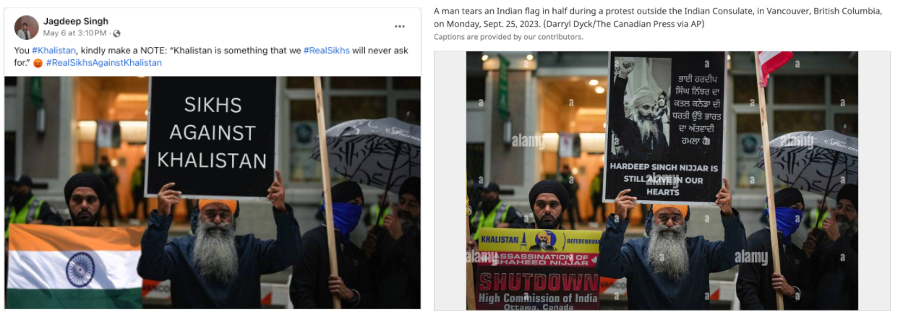

Accounts in the network used manipulated or fake images to amplify its messaging. For example, in Figure 13, the image posted by one of the accounts in the network shows a Sikh person carrying a sign that reads “Sikhs against Khalistan”. This has, however, been manipulated. The sign the man on the left is carrying has also been manipulated and edited as an Indian flag. The original signs were about the killing of a Sikh activist, and the photograph was taken on 25 September 2023 by the Associated Press.

Figure 13: Screenshots of a post from an account in the network that has manipulated an image to read “Sikhs against Khalistan” and an Indian flag (left), and the original image (right).

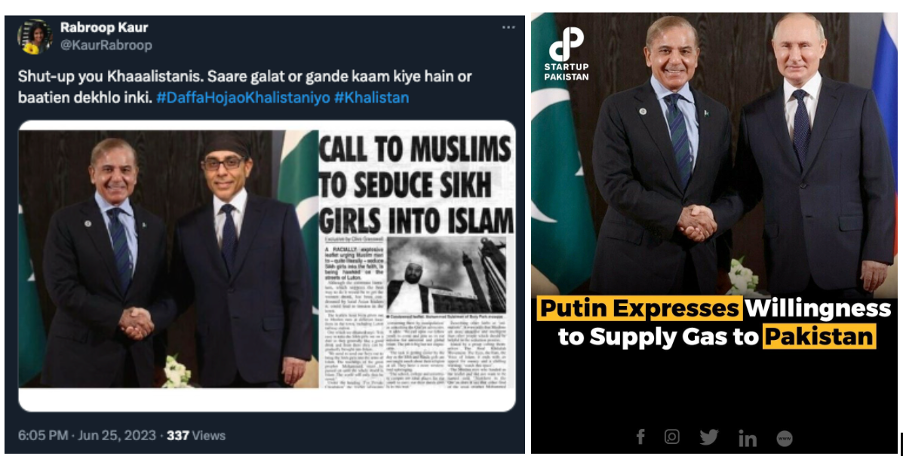

Another image shows Pakistan’s prime minister, Shehbaz Sharif, allegedly meeting Sikh activist Pannun. However, this was originally an image of Sharif with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Figure 14: Screenshots of a post from an account in the network that has manipulated an image to claim Pakistan’s prime minister is shaking hands with a Sikh activist (left). The original image is of Pakistan’s prime minister meeting the Russian president.

Network narratives

The network identified in this research was primarily focused on pretending to be Sikhs in India and labelling Sikh independence and human rights activists as “extremist”. However, there were several ways this was conveyed through divisive narratives. Below are some of the main narratives identified in the network, and the groups and individuals targeted.

Claims of “manipulated Sikhs” in diaspora

The network attempts to use issues in the news, events, or memes to target activists in diaspora Sikh communities in Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States or Australia. In some cases, there are references to Khalistan supporters as “aliens” in “far off lands”. Some of the posts claim that Khalistan was a “fantasy established by Pakistan” and that there are “manipulated Sikhs living in Canada, US and UK”. Further examples of this content can be seen in Figure 15.

Figure 15: Screenshots of posts from X showing references made by the network to Sikh communities abroad.

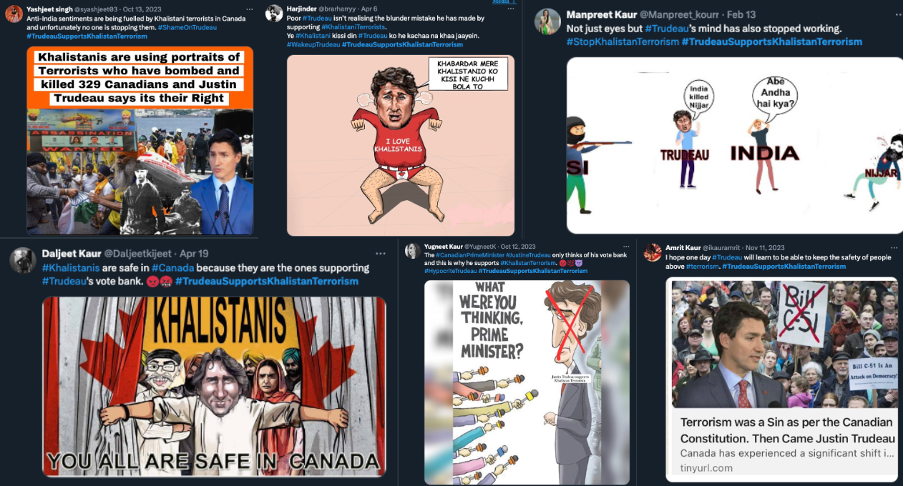

Targeting Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau

The network’s focus on Sikh activists abroad extended to numerous related subjects. For example, many posts in the network alleged that Canada and the UK were harbouring extremism. The screenshots in Figure 16 show a sample of the posts identified on X that claimed Canada and its prime minister were harbouring or covering for “Khalistani extremists”.

Figure 16: Screenshots of posts from X showing references made by the network to Canada and its prime minister.

Claims of Khalistani propaganda “silencing real Sikh voices”

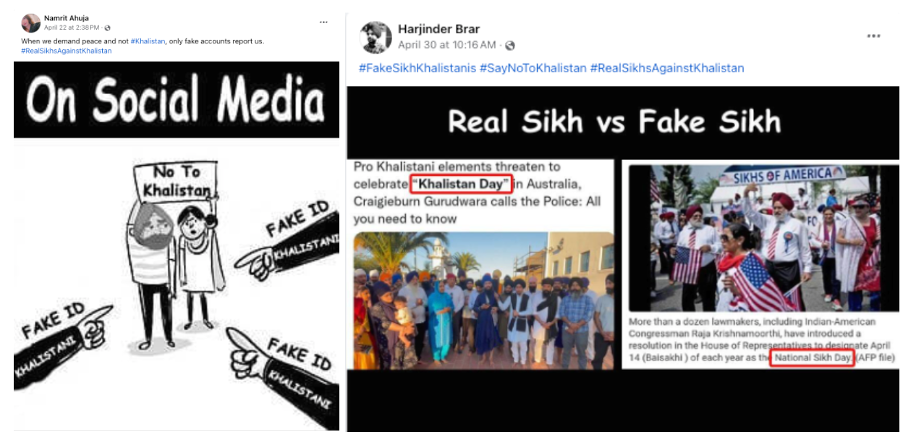

The network claimed that propaganda was flooding social media and “silencing real Sikh voices”. This form of rhetoric indicates an attempt to cause division within the Sikh community and sow confusion over what is real, and what is not.

Figure 17: Screenshots of posts from X showing references made by the network alleging other online sources of Sikh propaganda.

This same rhetoric has been echoed by numerous accounts on Facebook. The posts, as shown in Figure 18, allude to all accounts being propaganda and fake except for the accounts that do not want Khalistan.

Figure 18: Screenshots of posts from X showing references made by the network to “real Sikhs” and “fake Sikhs”.

Targeting Sikh activist Gurpatwant Singh Pannun

In some instances, the narratives shared by the network relate to on-the-ground events, specifically the foiled assassination plot against Sikh activist Gurpatwant Singh Pannun in 2023.

All of the accounts in the network used various themes to target Pannun and label him as an extremist. Examples of this include allegations of Pannun being sponsored by Pakistani intelligence and claims of the Sikh community labelling Pannun as a “terrorist”.

Figure 19: Screenshots of posts from X showing references made by the network to Sikh activist Gurpatwant Singh Pannun.

The network appears to be coordinated in its attempts to label Pannun as an extremist and stoke tension by claiming the Sikh community also believes this. Examples of this content can be seen in Figure 20.

Figure 20: Screenshots of posts from X showing references made by the network linking Khalistan to extremist views.

Conclusion

This investigation has revealed a coordinated influence operation designed to undermine Sikh activists and their efforts by posing as authentic members of the Sikh community. The network of fake accounts, spanning major social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and X, employs a range of tactics from using real celebrities’ images to posting uniform content laden with manipulative imagery and hashtags. Despite previous actions taken by social media companies to dismantle similar networks, the persistence and resilience of these actors underscore the challenges in permanently curbing such activities.

The creation of new accounts following the takedown of the previous network highlights a troubling trend: the ability of these influence operations to quickly regenerate and continue their campaigns. This new network, consisting of at least 53 identities and over 100 accounts, demonstrates a meticulous effort to appear credible through the use of realistic Sikh names and authentic-looking profiles, which have garnered considerable followings.

The primary aim of this network is clear – to delegitimise and discredit Sikh activists and the broader Sikh independence movement by labelling them as extremists and promoting narratives favourable to the Indian government. The targeted harassment of prominent figures such as Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, especially in the wake of an assassination attempt, illustrates the lengths to which these actors will go to stifle dissent and shape public perception.

This research underscores the necessity for ongoing vigilance and proactive measures by social media platforms to identify and dismantle such networks. It also highlights the need for greater transparency and accountability in digital spaces to protect the integrity of public discourse and the rights of individuals to advocate for their beliefs without fear of manipulation or retribution.

As this investigation has shown, continuous efforts are required to safeguard the digital landscape from such malign influences.