A video emerged online from November 2021 showing Myanmar military soldiers leading an attack on a village in Myanmar’s north.

Myanmar Witness has geolocated, chronolocated and verified the footage, adding English subtitles to make it more widely accessible.

The footage gives a rare, first-hand glimpse into the mindset of soldiers during a raid on a village. More than that, it reveals – through action and dialogue – the highly toxic culture of a specific Light Infantry Division, LID-101, which clearly allows and encourages the following forms of illegal behaviour:

the use of fire to destroy homes, entire villages, and places of worship

the arbitrary detention at gunpoint of civilians

the summary killing of anyone suspected of associating with anti-SAC forces

Figure 1: The person who films most of the footage appears in front of camera at one point saying, “It’s LID-101, let’s fight!”

Filmed by the perpetrators, the video shows military personnel leading an attack on Min Ywar village and repeatedly exhorting eachother to make LID-101 proud with their viciousness.

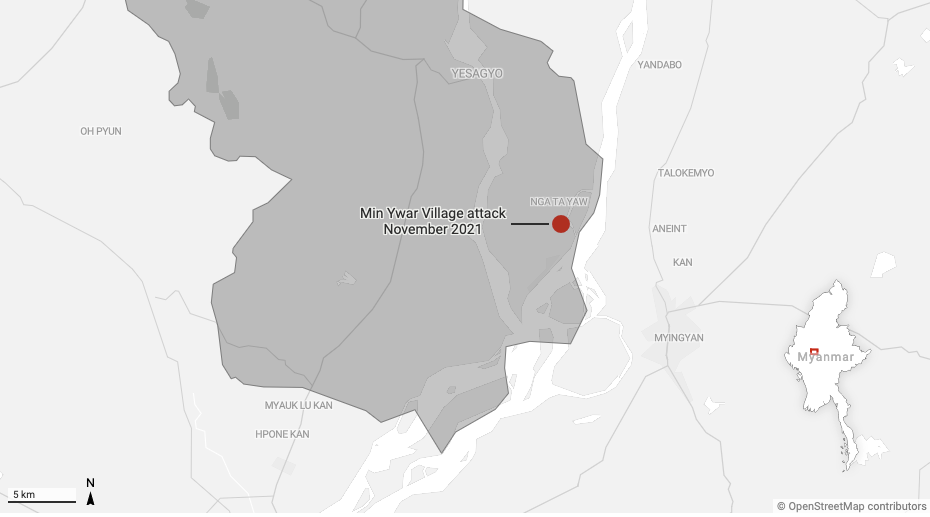

Figure 2: location of Min Ywar village.

After attacking and storming the village, the soldiers

Intimidate civilians

Threaten to burn the village down

Start destroying the villagers’ motorbikes

Detain civilians at gunpoint, forcing them to kneel

The video (source), translated and analysed by Myanmar Witness, is one of the strongest pieces of evidence showing the repeated intention of Myanmar military units to cause widespread and indiscriminate harm within civilian communities.

While there has been no official admission of responsibility by Myanmar’s military for the widespread razing of villages since the coup in February 2021, this video provides clear evidence of the mindset and underlying culture that enables these acts.

Watch the full video below, (thirteen and a half minutes) or click any of the timestamp links (00:00) in this report to open the video at the moment being discussed.

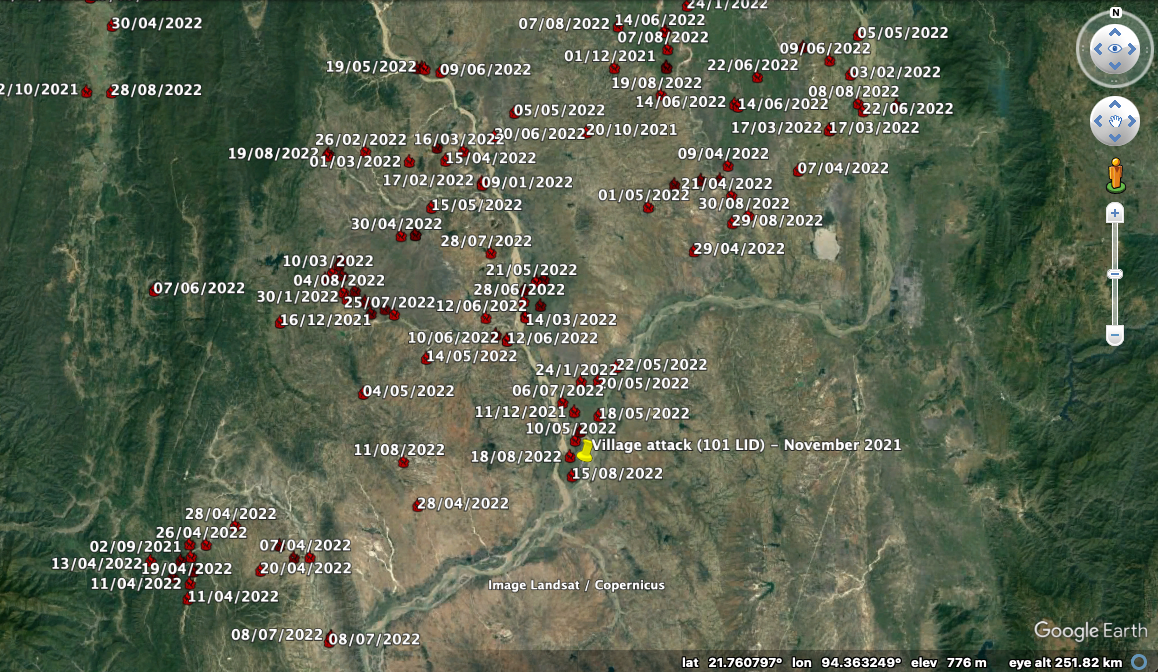

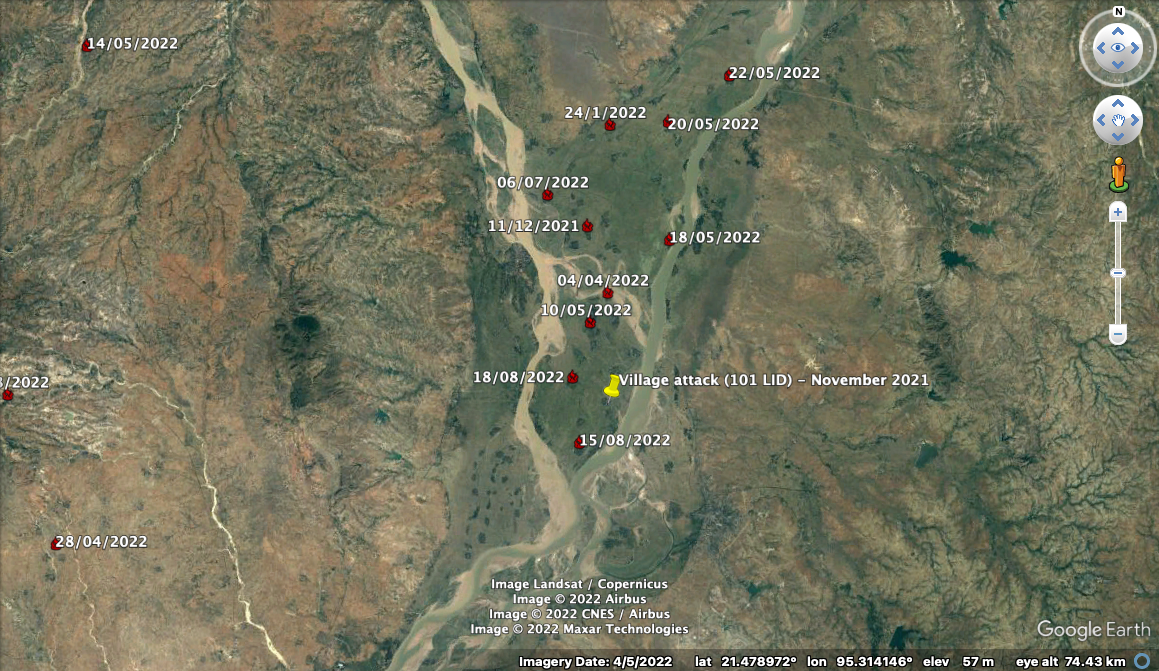

Through open source analysis of the footage, Myanmar Witness established where and when this attack happened. This analysis is significant as it provides an insight into other similar attacks on communities in Myanmar, especially those attributed to the 101 LID (Light Infantry Division), which have been widely reported in the region.

The content of this report should be taken into consideration along with a large number of other claimed attacks and illegality allegedly linked to 101 LID in the region, as can be explored on our interactive map of LID-101 mentions, pictured below.

Figure 3: map of media and social media mentions of sightings, incidents and allegations relating to 101 LID.

Further analysis of the town also shows that it was subsequently used as a position for a mortar base in close proximity to cultural and civilian buildings, indicating a further potential breach of international humanitarian laws.

Establishing where the attack happened

While the footage is grainy and low quality, there are some specific features viewed in the scenes that reveal specific details about the location where this video was filmed.

Our analysis shows that the village targeted in this attack was Min Ywar (မင်းရွာ) in Myanmar’s Magway State.

At 04:52 in the footage, a bridge just south of the village can be seen [21.532994, 95.312229].

Figure 4: geolocation of bridge seen in footage.

At 06:50 in the footage, a pagoda and building can be seen when the soldiers enter the village.

Figure 5: geolocation of pagoda and buildings seen in footage.

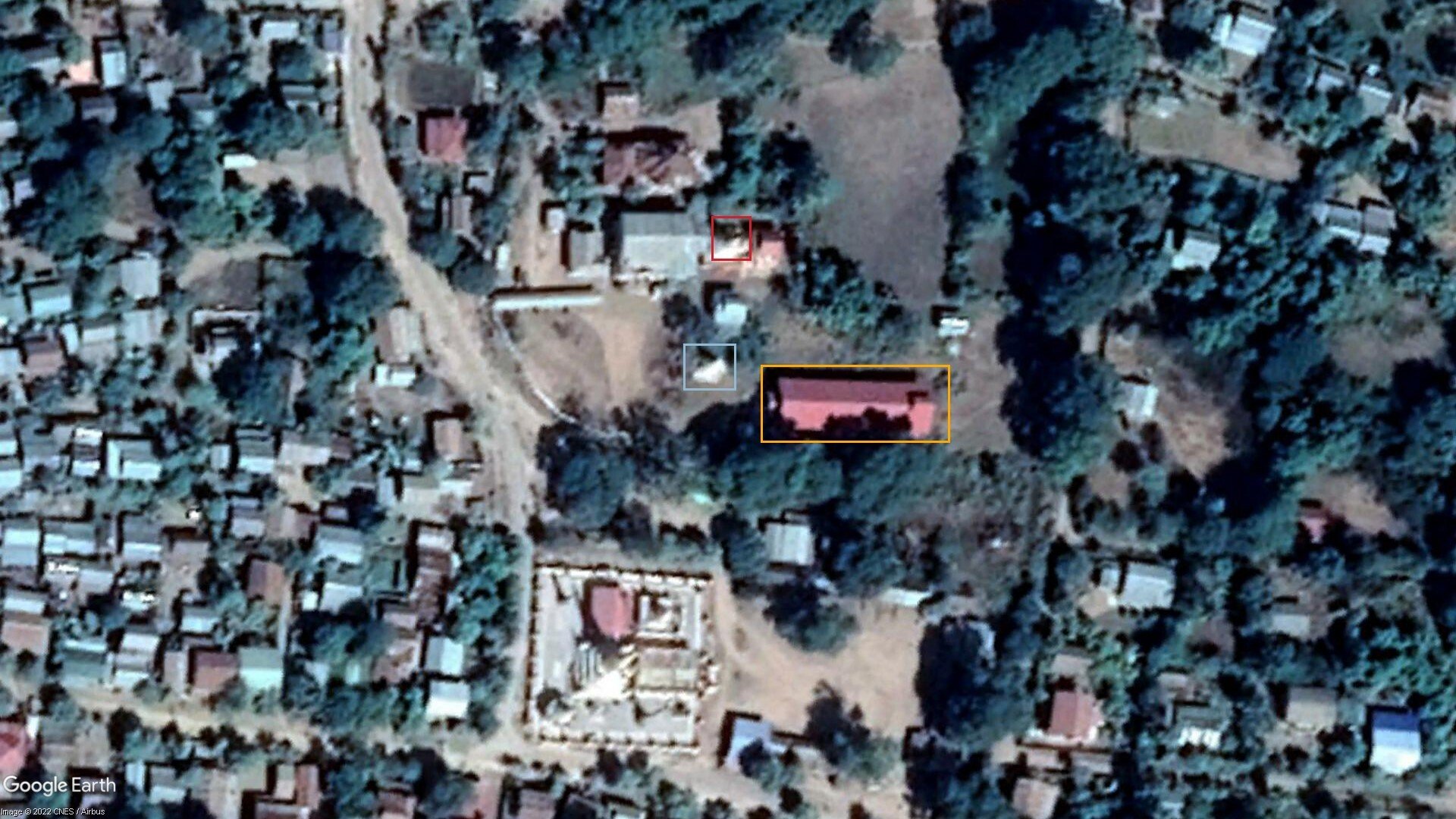

A geospatial analysis of the area using the available footage shows people were brought out from where they were seeking shelter to the centre of the three buildings seen below. Many of the civilians appear to have been hiding in the building marked in orange. The footage captured the civilians being forced out of the building by the military members.

Figure 6: geolocation of buildings using scenes from the footage.

By drawing together the different locations identified within the footage, and the time taken to move from one identifiable place to another, Myanmar Witness was able to verify that the events took place in Min Ywar village.

Finding when the attack happened

Through visual clues revealed in the footage, as well as local media reporting surrounding the attack’s location from local media news outlets, this analysis concludes that the attack on the village in Magway happened in November 2021.

A number of reports surfaced in November 2021 indicating that attacks were happening in Magway, carried out by the Myanmar military. In one report, there were indications that after an attack on 17 November 2021, two women and eight men were taken from a village and used as human shields.

There were also reports of military activity countering anti-government militia groups in the area before, during and after 17 November 2021.

Reporting from Myanmar Now indicates that this might not have been the only village targeted by the 101 LID, and claims that more than 11 villages were targeted during searches for anti-government militia.

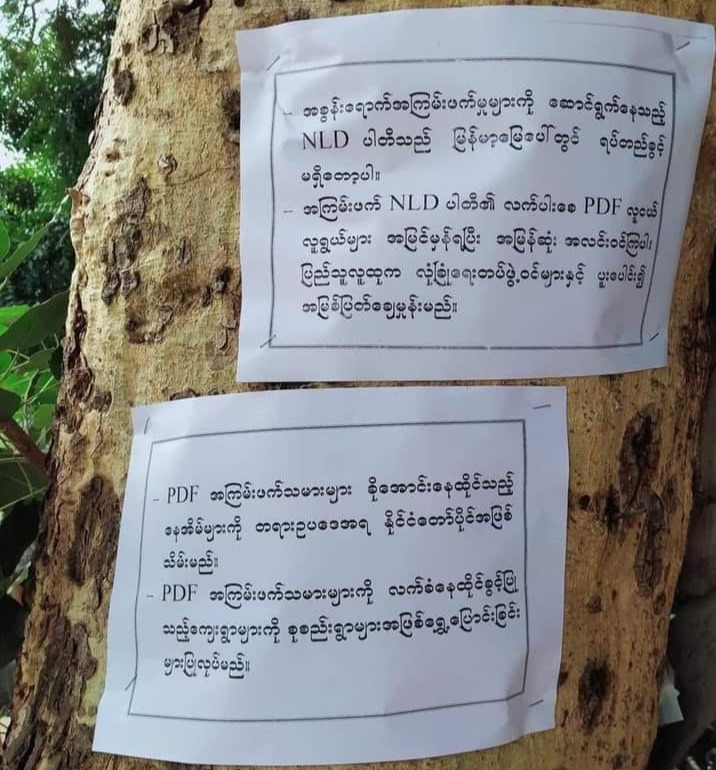

In the same area, there were also posters put up by local pro-military groups threatening anti-military groups and any associates of the People’s Defence Force (PDF). For example, the figure below shows posters which were allegedly placed in Magway around the same time as the attack on the village. They read as follows:

Top pamphlet: “NLD party which has been committing terrorism acts can no longer stay on Myanmar’s soil. We urge PDF – the terrorist NLD’s wing – to turn itself in or civilians will cooperate with security forces and destroy.”

Bottom pamphlet: “Houses where PDFs hide will be confiscated and become the property of the state. Villages which allow PDF terrorists to stay will be labeled as collaborating villages and relocated.”

Figure 7: pamphlets posted online, allegedly distributed around Magway around the same time as the attack in the footage.

To identify when the footage was filmed, analysts at Myanmar Witness undertook a two-fold process. Firstly, analysts looked at environmental factors, including indicators of weather, field colouring and fauna. Secondly, once a rough time frame was established, the window of time was narrowed down by analysing the shadows seen in the footage.

First, in some of the scenes of the video, different coloured fields can be seen. Namely, one field appears more green, while another appears yellow and more muddy. This can be seen to match imagery from November 2021.

Figure 8: fields seen in footage (left is yellow mud field, right is green).

This type of field colouring and vegetation is only seen at certain times of the year. The satellite image below from Sentinel Hub, shows the fields on 21 November 2021. The colour of the fields in this image appears to match the colouring of the fields visible within the footage.

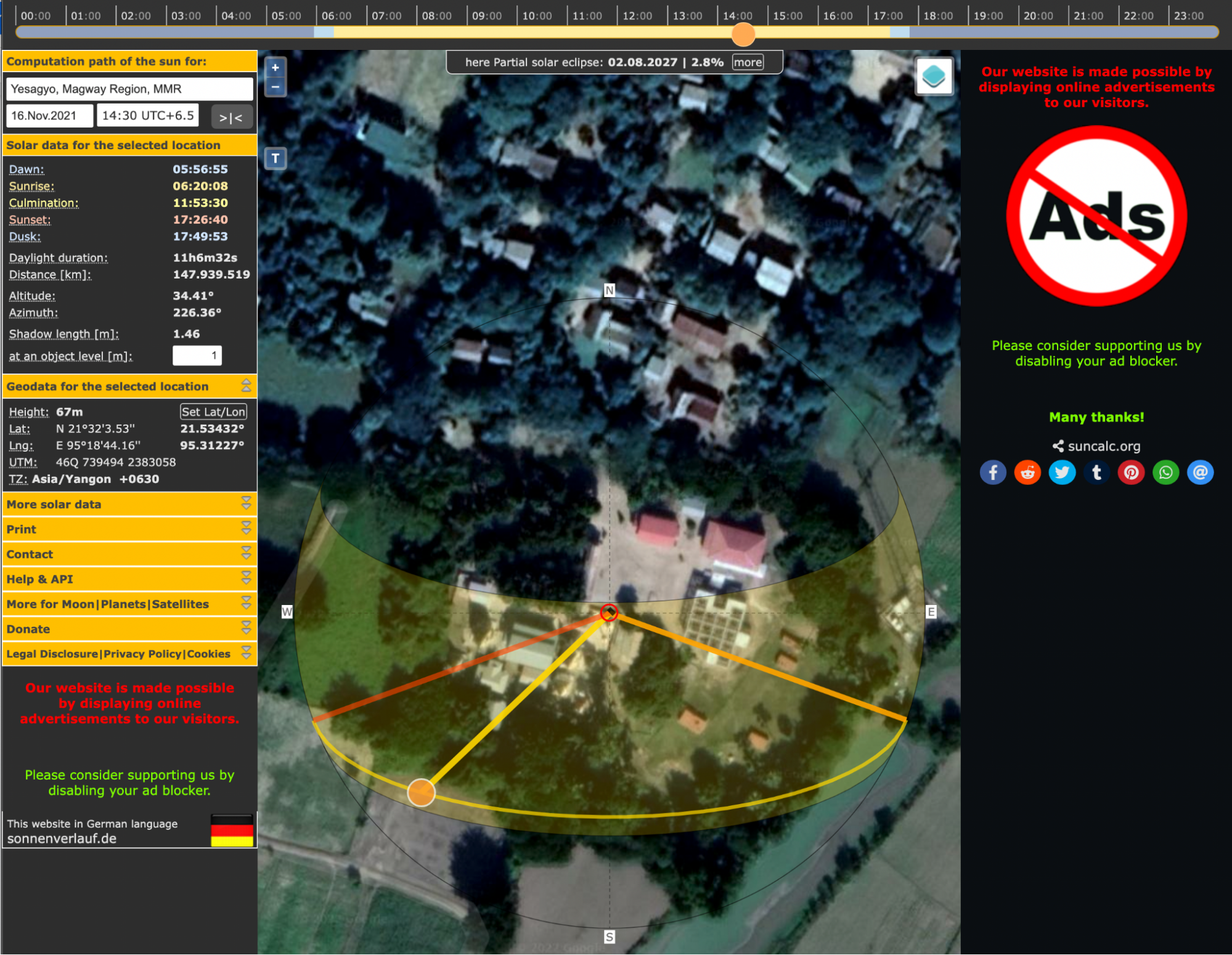

While the fields may be indicative of a November 2021 date, further verification was needed to confirm this timeframe. Through an analysis of the shadows, Myanmar Witness analysts were able to show a clear match with a November 2021 timestamp.

At 07:51 in the footage, shadows from the Buddhist temple spires are visible, allowing investigators to digitally verify a possible chronolocation – identification of time – as to when the fighting took place.

Figure 9: shadows seen in the footage, cast by buildings.

By using Google Earth, this analysis shows the shadow from the Buddhist temple spires was projected at a bearing of 223 degrees.

Figure 10: Google Earth screenshot showing the angle of the shadow.

Once the angle of the shadow was calculated, it was possible to determine the time of day the attack could have taken place using Suncalc – a generative calculator that allows calculations of time based on the angle, and length, of shadows. In the screenshot below, the shadow matches the trajectory shown between 2 and 3pm on 16 November 2021.

Figure 11: screenshot of Suncalc matching the angle of shadow and time of day to November 16. Suncalc link here.

Myanmar Witness believes that it is highly likely that this attack took place on 16 November, due to the analysis of environmental factors, such as the field colouring, and reports from local media, which were cross-referenced against the shadow analysis.

Arms analysis

Analysis from the team at Myanmar Witness has identified the following weapons in the footage:

MA-4 mk. I assault rifle x2 (with a possible 3rd)

MA-3 mk. II assault rifle

UBGL (under barrel grenade launcher 40mm)

MA-7 (60mm mortar with a range between 3270 and 4600 metres)

Weapon usage and Video Walk-through

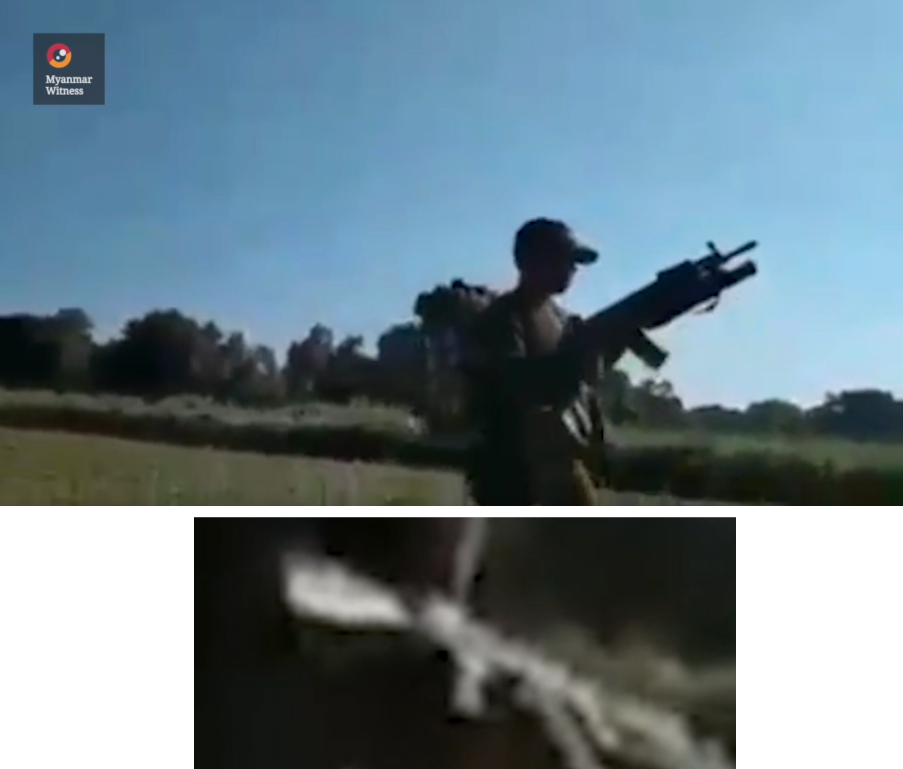

At 01:16 in the footage a distinctive sound from an explosion in the distance can be heard. As a soldier lowers the weapon that made the sound, there is a clear view of the system. It is possible to identify it as a MA-4 assault rifle, which has an integrated 40mm Under-Barrel Grenade Launcher (UBGL). The first time the same sound from an explosion is heard in the video is at 00:36.

Figure 12: screen capture from the moment of the sound of the first explosion at 00:36.

Both before and after the shot at 01:16 the same soldier is seen kneeling with his rifle pointing upwards. It is likely the soldier is reloading the UBGL, where the grenades have to be inserted in the back of the UBGL’s receiver (as shown in the third image below).

Figure 13: images of weapons cross-referenced against images from the video.

The technical indications the MA-4-armed soldier is receiving – while he is reloading his UBGL – are consistent with his weaponry and with how he is employing it, as the person filming orders him to “tilt it up” in an effort to correct his trajectory.

Figure 14: screen capture shows instructions being given to correct the trajectory at 01:23.

At 02:55 it is possible to spot another soldier carrying an MA-4 assault rifle. The soldier wears a baseball cap and carries a light-coloured backpack. Its barrel assembly is breached forward, suggesting it was fired and is now about to be reloaded. The cameraman directly asks the soldier for a “40”, in reference to the 40mm calibre of the UBGL-launched grenades.

Figure 15: screen capture shows soldier asking for ammunition.

As the second MA-4-carrying soldier comes closer to the officer we can have a better view over his MA-4: the straightness of the stock and limited length of the barrel indicate it is a MA-4 Mk. I model.

Figure 16: screen capture from the video showing a rifle.

Starting from 03:07 it is possible to see the same soldier taking out what appears to be a 40mm grenade from a torso pouch and as he is about to load it into his UBGL the grenade falls on the grass. He then calmly crouches down to pick the round up again and moves it upwards and towards his rifle.

Figure 17: additional screen captures from the video showing a soldier carrying a rifle.

Until now, it was possible to identify at least two soldiers armed with MA-4 rifles, with a third one hard to confirm due to the video’s poor quality. Apart from the use of the UBGL, the audio allows it to determine that small arms have been used in full-auto bursts (especially from 00:00 to 00:36) or semi-auto fire.

At 04:23 a very characteristic skeletonised stock allows for the identification of an MA-3 assault rifle.

Figure 18: screen capture shows an MA-3 assault rifle.

At 04:40 another MA-3 assault rifle can be seen. A quick view of the rifle’s rear iron sights allows it to identify it as a Mk. II version.

Figure 19: Screen capture shows an MA-3 Mk. II assault rifle.

At 10:40, once inside the village, a third soldier armed with an MA-3 assault rifle can be seen, again because of the distinctive skeletonised stock.

Figure 20: Screen capture shows another MA-3 assault rifle..

At 11:45 the cameraman calls to another soldier that according to him is carrying an “MA-7”.

Figure 21: Screen capture shows the exchange about the MA-7.

According to several official Myanmar military documents outlining armament and equipment for infantry units, corroborated by OSINT material collected and analysed by MW, the MA-7 is a 60mm mortar with a range between 3270 and 4600 metres.

At 11:29 it is possible to see a man belonging to the party who walks by the camera carrying, in his open backpack/basket (for quick and easy access) a metal tube consistent with the dimensions of the 60mm MA-7 mortar, with, next, and visible even better at 11:32, the mortar’s metal bipod.

Figure 22: Screen capture of likely MA-7 in backpack.

Footage indicates link to use of fire in villages by 101 LID

Statements made by the soldiers who identified themselves as members of the 101 LID indicated that they would burn down the entire village if it was found to be associated with the PDF. These statements were made a number of times throughout the footage.

At 09:40 in the video, a person can be heard saying “burn the whole village”, at 12:35 in the video, one soldier states: “We’ll burn down everything if it’s a PDF village”.

Figure 23: “We’ll burn down everything if it’s a PDF village.”

Since September 2021, Myanmar Witness has monitored fires in Myanmar, including the intentional burning of villages. In the area surrounding Min Ywar village in Yesagyo Township several villages suffered the fate that was threatened in the footage. They were burned down, or had multiple buildings within them damaged and burned to the ground.

The two figures below show reported and claimed fires in villages and towns surrounding Min Ywar, including the dates they were either verified or reported to have occurred. This shows just how thematic the scale of damage has been to civilian communities in areas in the region, many of which involve similar activity as seen in the footage analysed in this report.

Figure 24: Google Earth screenshot of the wider area of verified and claimed fires surrounding the Yesagyo area.

Figure 25: Google Earth screenshot.

As seen above, our mapping of both verified and claimed fires and use of fire in the attacks on villages indicates a widespread and systematic use of fire against communities, the same standard operating procedure that was threatened by the soldiers from the 101 LID in the footage.

Figure 26: “Burn the whole village!”

Burning of motorbikes – related to other unattributed attacks in Myanmar

The 101 LID soldiers also made additional threats in the footage, including threats to destroy motorbikes. Motorbikes are essential for the livelihoods of rural communities as they provide not only affordable transport, but access to markets. While destroying freedom of movement might align with the Myanmar military’s goal to prevent uprisings and PDF activity, it also has long-lasting impacts on the development of rural communities.

At 07:11 in the footage, one of the soldiers can be heard saying “destroy the motorbikes here, let’s burn them!”.

Figure 27: “Destroy the motorbikes here, let’s burn them!”

Although the footage doesn’t capture evidence of the 101 LID actually destroying the motorbikes in Min Ywar village, Myanmar Witness has analysed a number of similar attacks in other locations in the past. For example, in the case of Yinmarbin on 14 August 2022, our analysts documented a massacre in Yin Paung Taing village (ရင်ပေါင်တိုင်) as well as the intended destruction of civilian vehicles.

Figure 28: geolocation of destroyed vehicles in Yin Paung Taing village (ရင်ပေါင်တိုင်) [22.073258, 94.789230]

Importantly, this was also identified by our analysts in the monitoring of attacks in Thantlang, which had been repeatedly targeted, reportedly by military units.

Figure 29: destroyed vehicles seen in Thantlang.

These statements made by the 101 LID provide a clue which aligns with a pattern of events seen across the region, and indicates a standard operating procedure. Myanmar’s military destroy vehicles in villages and towns as a way to punish the community and stop those suspected of being against the military from getting transport for supplies or fleeing the region.

Subsequent use of Min Ywar Village as a military position

Following on from the attack, Myanmar Witness has found that the village became a position for the military to set up at least one mortar system with a surrounding bunker. This mortar position is located less than 20 metres from both a cultural site as well as a building referred to as a monastery.

Drone footage filmed by PDF-allied groups over the village in late 2022 shows the village occupied by what is believed to be Myanmar Military. In the footage, at least one clear mortar position with surrounding defences can be seen at about 12m from the walls of the pagodas, a cultural building.

Figure 30: drone footage showing mortar position.

High resolution satellite imagery from Planet, taken on November 29, 2022, indicates the position is still present in the same location.

Figure 31: Planet satellite image showing mortar position on November 29, 2022.

The location of military objects near or within a civilian area, as well as within close proximity of cultural objects is a questionable practice and may constitute a breach of international humanitarian law.

Conclusion

This footage provides a rare glimpse into the minds of Myanmar military personnel. Although the footage itself doesn’t show the burning of the village or destruction of vehicles, these types of attacks have been widespread and systematic across Myanmar’s northern region since the February 2021 Coup.

Following a geolocation and chronolocation of the events captured within the video, Myanmar Witness believes that this footage was filmed in Min Ywar village, on 16 November 2021.

When this evidence is placed alongside the multiple reports Myanmar Witness has already published which show the razing of villages suspected to house PDF, the threats to PDF-sympathisers seen through warning pamphlets, or the destruction of vehicles, it reveals the military’s standard operating procedure. For the first time, it was possible to capture the intent of the individuals involved in such attacks on film – ironically, their own film.