Warning: Graphic. This report contains graphic imagery and links to graphic imagery shared online. While efforts have been made to blur details, the report contains information which some readers may find distressing.

Key Event Details

Date/Time of Incidents:

146 separate events between March 2022 and September 2023

Alleged Perpetrator(s) and/or Involvement:

Myanmar Military (SAC)

People’s Defence Force (PDF)

Summary of Investigation:

Myanmar Witness has identified, documented, and, where possible, verified local media reports and User-Generated Content (UGC) related to the burning of bodies between March 2022 and September 2023. This includes bodies burnt post-mortem, people allegedly burnt alive, and people who died as a result of arson, or munition and airstrikes.

146 separate events have been catalogued. Although many events were unverifiable, 80 events had unique imagery of the victims.

The majority of reported events were in the Sagaing Region. This area is a conflict hotspot, as seen by other Myanmar Witness reporting.

There has been a decrease in reporting of events involving the burning of bodies over time. The exact reason for this remains unknown.

35 cases (24%) mentioned female victims, including reports of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV), deaths and other potential violations of international law.

Myanmar Witness believes the burning of bodies, pre or post mortem, could represent a violation of international law and recommends international legal bodies investigate this further.

Executive Summary

Before and since the start of the February 2021 coup, many violent events have occurred in Myanmar, including burnt villages (as reported by the Ocelli Project and within Myanmar Witness reports), beheadings, and abundant airstrikes. Through the collection and analysis of user-generated content (UGC), Myanmar Witness has investigated, verified, and reported on potential human rights violations associated with the conflict across Myanmar. By doing so, Myanmar Witness identified several claims related to the burning of victims, alive or deceased, intentionally or indirectly.

Myanmar Witness has investigated events between March 2022 and September 2023 involving burnt bodies. 146 separate events were identified which included burnt bodies. Unique imagery of the victims was available for 80 of these events. Of the 444 victims identified, 150 victims were visible within UGC. The events were categorised as:

Burnt alive

Burnt indirectly

Burnt after death

A number of events did not fall into these three categories, which were marked as “other” (such as Sexual and Gender Based Violence (SGBV) and one with imagery of a relatively standard cremation), and events with limited information were marked as “unclear”. Of the 146 events, 104 occurred in Sagaing, a region that has been a hotspot during the conflict. Magway State was the second most common location, with 21 cases. Additionally, 35 events specifically mentioned a female victim.

Four case studies have been further investigated to show the different nature and intensity of the events. This includes: piles of bodies, child casualties, and victims with significant wounds. This investigation has revealed the mutilation of bodies, disrespect for the dead and the infliction of untold suffering on the civilian population; activity which could violate multiple international laws.

According to various reports, the SAC were allegedly involved in many of these cases. Myanmar Witness cannot yet verify this but will continue to monitor any developments in order to assess responsibility.

Background and Context

While cremation and accidents involving fire do occur, fire can also be used strategically and horrifically in warfare. Myanmar is no exception. Examples of these events include the religious cremation of residents, common housefires, but regretfully also the victims of warfare, burnt in arson attacks, burnt post-mortem, or burnt alive. The impact can be deadly; for example, it can take lives, trigger forced displacement, or have coercive effects on population groups.

While international law and norms stipulate the need to avoid superfluous injury, unnecessary suffering, harm to, or the targeting of, civilians (e.g. Geneva Convention, Additional Protocol II, Article 13(2), ICRC Handbook, Rule 70), the conflict in Myanmar has seen many potential violations of these rules. Additionally, customary law outlines a shared belief that spreading terror among a civilian population is unacceptable (ICRC Handbook, Rule 2), and binding international agreements provide further protection for civilians.

The burning of bodies, pre or post-mortem, could also constitute a violation of international law. Mutilation is prohibited in many international laws (e.g.: Lieber Code, Article 56; Geneva Conventions, common Article 3; Third Geneva Convention, Article 13; Fourth Geneva Convention, Article 32; Additional Protocol I, Article 75(2); Additional Protocol II, Article 4(2); and ICC Statute, Article 8(2)(b)(x) and (e)(xi)). Additionally, parties to the conflict must take all measures to respect the dead (Geneva Convention IV, Article 16; Geneva Convention, Additional Protocol I, Article 34(1); Geneva Convention, Additional Protocol II, Article 4) and personal dignity must also be protected (ICC Statute, Article 8(2)(b)(xxi) and (c)(ii)).

Since the coup started on 1 February 2021, protests have been common and civil disobedience organisations were formed. The Myanmar military has violently suppressed political opposition and has acted with violence against civilian communities. Over time, this conflict has spread and evolved throughout Myanmar, often even near the borders. In many cases, in areas where control is not a given, the tactic of using fire as a weapon has been used — likely as part of both the Myanmar military’s offensive against PDF groups and as an attempt to subjugate the civilian populations through terror and scorched earth methods. These events have not been solely witnessed since the coup but were used before the coup during the Rohingya genocide in Rakhine state. The scorched earth tactics were also utilised before these events in Myanmar, such as the 2011 Kachin conflicts.

Myanmar Witness has been identifying and verifying information regarding the use of fire, such as with Myanmar Witness Reports: Myanmar on Fire and Civilian Infrastructure and Food Supplies Destroyed in Myanmar Military Arson Attacks. Further reporting has been conducted specifically on the burning of bodies in singular events, like the Mon Taing Pin Massacre and the burnt vehicle events in Moso. As ongoing conflict monitoring revealed continued reports of human remains found at sites of fires, an investigation was set up to determine if any events could be verified.

For clarity, this report excludes cases of common housefires, religious cremations and other nearby subjects. This paper reviews events allegedly involved with the burning of any human or human remains in Myanmar, a consistent feature of the conflict. This report seeks to provide insight into this phenomenon by assessing data and specific case studies.

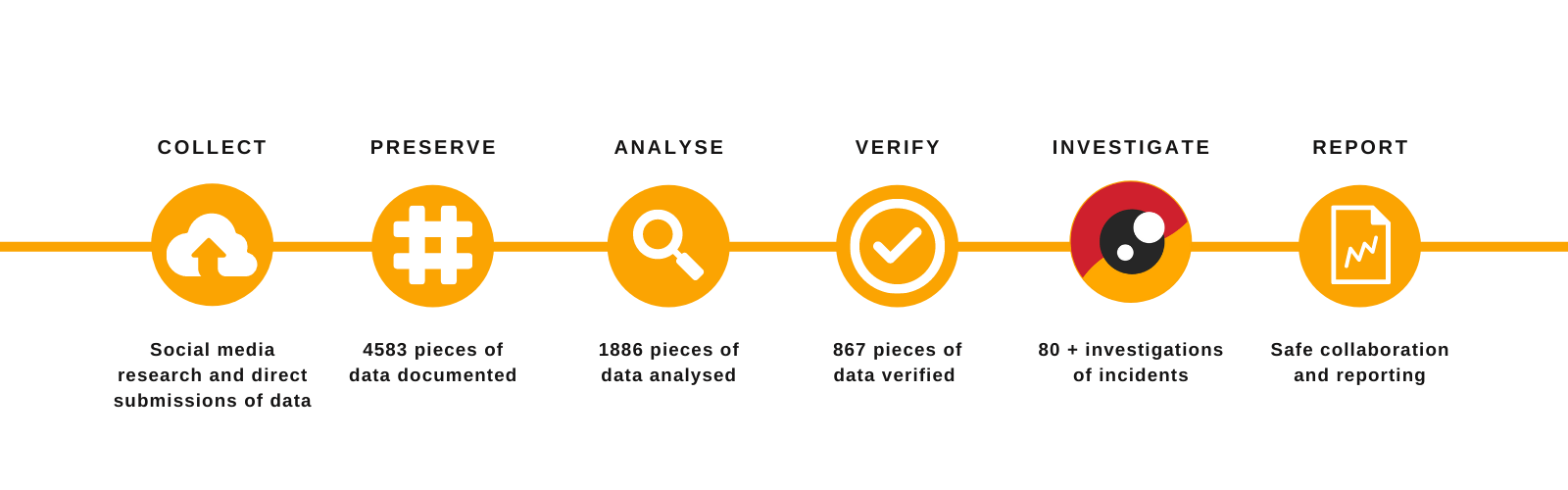

Methodology

Myanmar Witness follows a methodology of digital preservation and rigorous, replicable analysis. Digital evidence is collected and archived in a secure database and preserved with hashing to confirm authenticity and prevent tampering.

To read the Methodology, download the PDF.

Trend Analysis

To provide an insight into the events investigated, Myanmar Witness has analysed the data by location, event type, gender, time and trend outliers. The data featured below encompasses 146 events with 444 claimed victims, 160 of which were photographed.To read the full trend analysis, download the PDF.

Case studies (Graphic)

Myanmar Witness has selected four events to demonstrate the different types of incidents identified during this investigation. Each event was chosen because of its clear visuals, which aided the verification process. Where possible the images were geolocated. A more complete description of these geolocations is available in Appendix V (download the pdf). The uncensored images can be found in the respective links or upon request.

Case study 1

8 victims reportedly burnt in Tabayin, Sagaing, on 4 March 2022

Eight young people were reportedly killed and burnt on 4 March 2022 (Event 4 in the dataset). Sources claim that nine men and one woman were involved in the incident. Analysis of UGC shows four dead bodies (in imagery alike figure 7) that have been severely burnt. The damage includes charring on most of the body, burnt layers of skin, and missing parts of soft tissue.

Figure 7: A blurred image from the events in Tabayin township (event 4)

As the intensity of the damage done to each person differs, (i.e. some of the victims were partially burnt while others were unrecognisable) it is unlikely that the victims burn damage was caused by a flammable object. Similarly, it also appears that the fire wasn’t directly from the bikes, but from an accelerant like petrol. Whilst an incidental fire is still a possibility, it is unlikely for a number of reasons, including that the bodies are situated in between burnt motorbikes, a number of victims appear to have been burnt together, and there are no visible marks from dragging/movement near the victims. These factors suggest that the burning was committed out of a malicious nature.

One of the sources stated that after the bodies were burnt, some were shot again. Using purely the UGC, this claim cannot be verified, nor ruled out entirely.

Geolocation

While the following location has many features that match satellite footage, this location was unable to be geolocated as per Myanmar Witness standards for verification. That said, the possible coordinates for this location are 22.576856, 95.280002, which corresponds to Tabayin township, where the events allegedly took place.

Figure 8: An unverified geolocation of event 4 (22.576856, 95.280002)

Case study 2:

An alleged child victim burnt in Pale Township, Sagaing Region on 15 August 2022

A facebook account claimed (warning: graphic link) that there were seven victims of an incident (event 67 in the database), one of whom was seven-years-old. Only one body can be seen in the post. The image showed charring and missing soft tissue on the body. The flames appear to have burnt hotter or for longer than in case study 1, as indicated by the victim’s exposed bones. The victim may have been a child, as the body seems relatively small compared to its surrounding environment. However, a lack of reference objects limits the ability to reliably confirm whether this is a child.

Figure 9: A blurred image from the events in Pale Township (event 67)

Geolocation

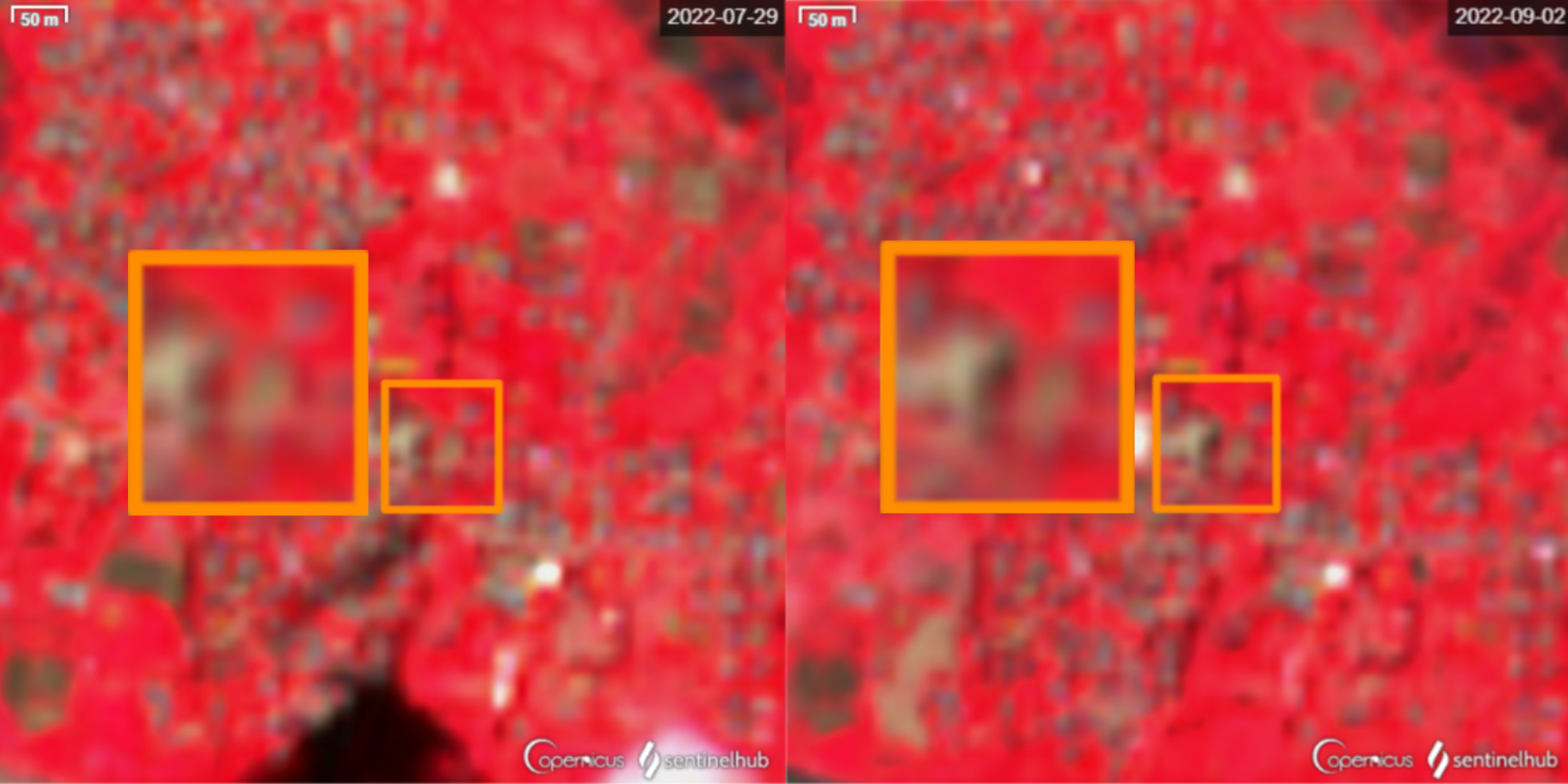

Multiple geolocated pieces of footage situated these events in Pale Township (coordinates of 22.072981, 94.789303). The geolocation was verified by visualising the buildings’ outline and the placement of foliage, as shown in figure 10.

It was not possible to chronolocate the footage, as clouds obscured all relevant satellite footage in the month of August 2022. Despite this, some of the later imagery still showed damage in the form of discolouration, as can be seen in figure 11.

Figure 10: A verified geolocation of event 67 (22.576856, 95.280002)

Figure 11: sentinel imagery showing some of the discoloration in the geolocated area.

Case study 3:

17 victims reportedly burnt in Htantabin Township, Bago on 10 May 2023

Claims that circulated on Facebook (event 127) mentioned that 17 victims were set on fire, including seven children (source redacted due to graphic nature, available on request). Myanmar Witness counted seven burnt bodies in the associated imagery. One source (redacted due to privacy concerns) also claimed that victims were burnt alive.

Figure 12: A blurred image from the events in Htantabin township (event 127)

In Figure X, the victims lower legs are intact. This could mean that the victims were stacked on top of each other before they were set on fire. Other victims appear to have been burnt in a different manner and location, as damage to these bodies is markedly different. Allegedly, the incident was a retaliation to nearby losses by the Myanmar Military, but this cannot be verified.

In the provided UGC, it appears that ethnic armed forces were allowed to gather the victims. This adds weight to the claims that the PDF were not behind the incident.

Geolocation

Using geospatial markers, the images of the victims were geolocated to Nyaung Pin Thar village (ညောင်ပင်သာ 18.601225, 96.597948). Unfortunately, chronolocation was not possible, as the fire was not visible on FIRMS or Sentinel satellite imagery.

Figure 13: A verified geolocation of event 127 (18.601225, 96.597948)

Case Study 4:

2 burnt bodies in Toke Gyi, Sagaing on 17 September 23

Images posted online showed two entirely burnt bodies, while a third features black, scorched marks on the face and body, including notable marks on the ankles (event 146 in the database; source redacted due to graphic nature of imagery, available on request). The wholly burnt victims share similarities to the first two cases mentioned (events 4 and 67). The victims died after the Myanmar Military allegedly set fire to the area, following clashes along the river between SAC boats and Kachin Independence Army.

Figure 14: A blurred image from the events in Tokgyi township (event 146)

Geolocation

The post featured a drone video of the town while it was on fire, which Myanmar Witness converted into a panorama image of the skyline. The ground proved difficult to verify, due to floods from the nearby Irrawaddy River; however, Myanmar Witness believes it took place in Toke Gyi village (တုပ်ကြီး) (24.302536, 96.453083). Related imagery can be found in the Appendix.

Figure 15: A verified geolocation of event 147 (24.301428, 96.456854)

Conclusions

This report has highlighted a significant number of events involving the burning of bodies during the conflict in Myanmar. The use of fire on human bodies, both directly and indirectly, could amount to violations of international law.

This research has sought to shine light on this type of human rights interference, showing its rate of occurrence. Although the frequency of events reported has gone down over the timeframe of interest, Myanmar Witness cannot confirm whether this is due to a decrease in events or a decrease in reporting. A notable amount (25%) of the events appeared gendered in nature. and the locations where these events occur most frequently. The case studies reveal the intensity of the events, with children reportedly among the dead, imagery of piles of victims, and multiple claims of people being burnt alive, be it indirectly (e.g. as a result of air/artillery strikes) or directly.

By far, the majority of the events occurred in Sagaing state (73% of the cases with victims were visible in UGC). Sagaing is part of the Dry Zone, an area of known resistance that Myanmar Witness has widely reported on as it represents the violent epicentre of the conflict. As such, the dry zone appears to be the main location of these crimes based on this investigation. Most of the events (86%) of the cases claimed SAC or Pyu Saw Htee as the executive actor.

The exact reason for these occurrences is still unverified, but a likely option is that the burning of bodies is used to spread fear or terror among the population, not only through the brutality of the acts, but also by preventing families from saying goodbye or giving their loved ones a proper burial.

Future Monitoring

Myanmar Witness will continue to monitor, identify, verify, analyse and report on the events involving the burning of victims of any party, with a particular focus on how they are performed. Myanmar Witness seeks to shed light on atrocities and determine attribution so that the responsible parties are held to account.