Executive Summary

Since the February 2021 coup, the Myanmar military has violently suppressed political opposition, set villages alight, and used disproportionate violence against civilians. As the Myanmar military struggles to exert control over areas of resistance, air strikes have become a key part of their offensive. This report by Myanmar Witness provides insight into the modus operandi of the Myanmar military.

To read the full report, download the PDF.

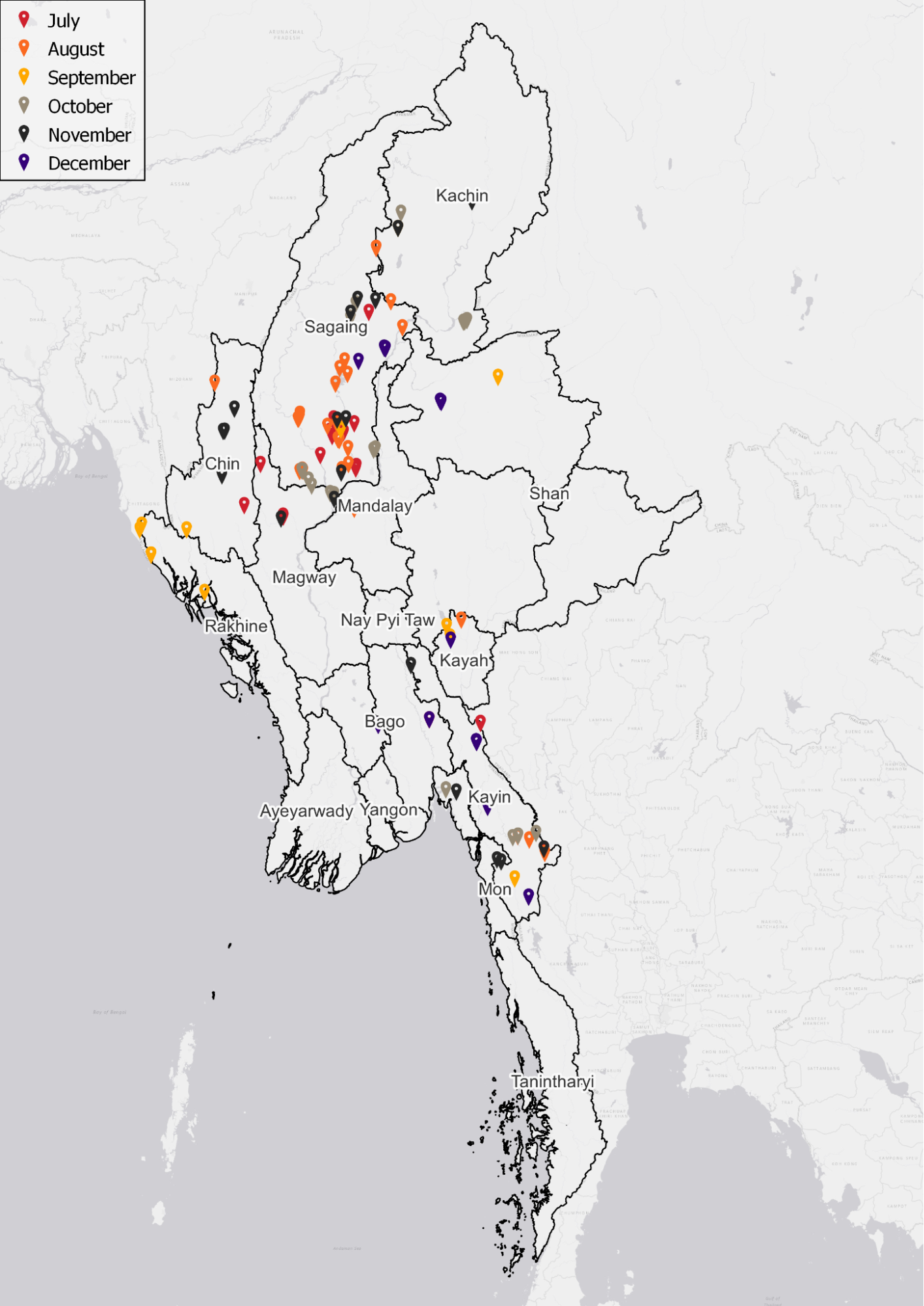

Figure: Map of AWIs by month, separated by colour. The highest concentration is located in Sagaing region. Map created with QGIS.

Through a quantitative study, Myanmar Witness has identified 135 airwar incidents (AWIs) over the six month period investigated. As each incident almost certainly represents more than a single air strike, it is clear that the Myanmar military’s airwar is fast becoming omnipresent in the lives of the people of Myanmar. Air strikes are an almost daily occurrence.

Reports of airstrike incidents were highest in August 2022. Although the data collection period for this report ended on 15 December 2022, the number of incidents during this month was above the average. Had data collection continued, Myanmar Witness believe that the number of incidents would have continued to increase.

Emblematic incidents including the airstrike on Camp Victoria, alongside ongoing monitoring by Myanmar Witness, indicates that airstrike allegations were increasing from September 2022 onwards.

Figure: damaged buildings at Camp Victoria following an airstrike.

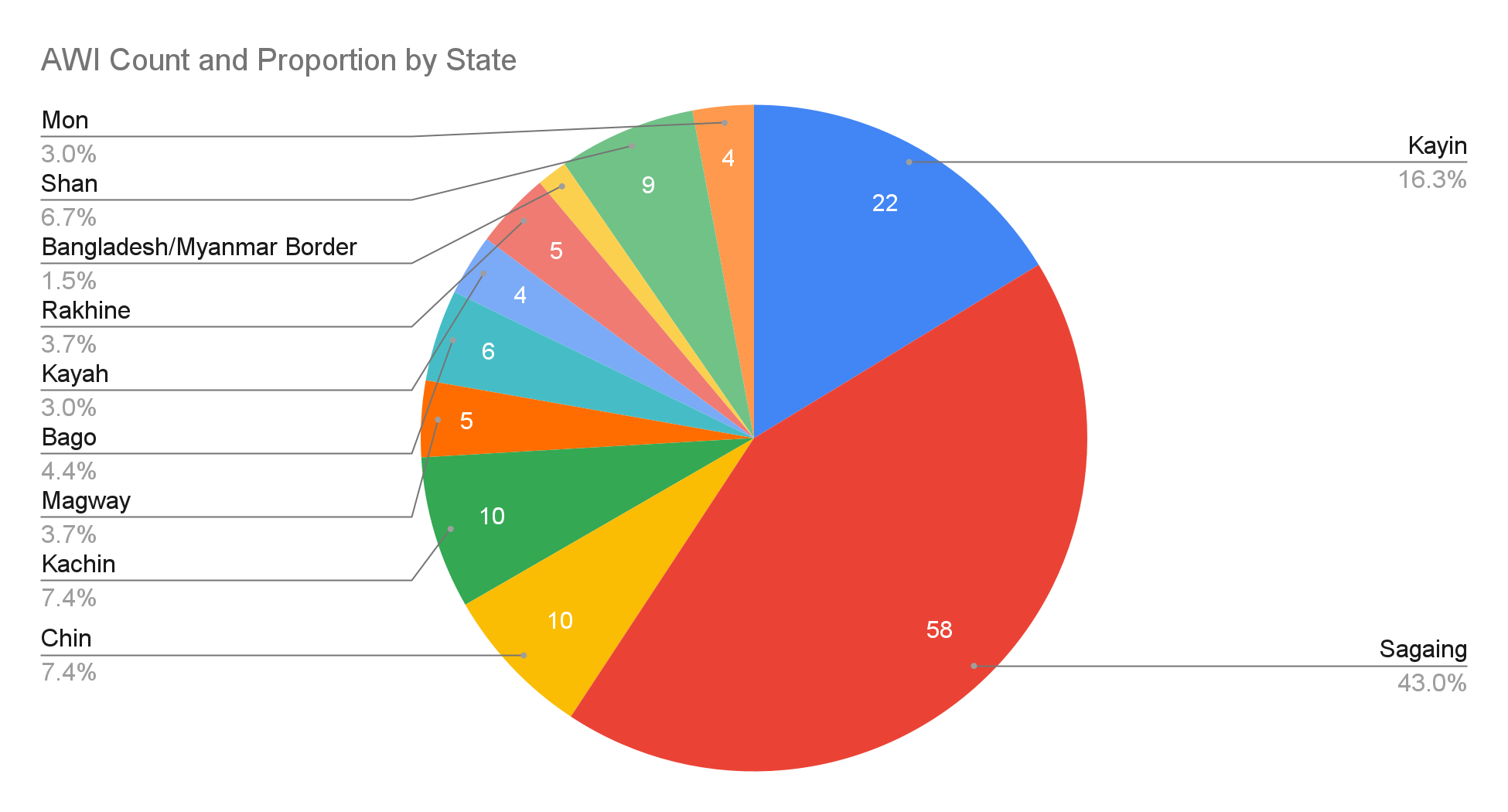

The areas with the highest concentration of airstrike allegations correspond with areas of known resistance to the Myanmar military. The highest number of airstrikes were reported in the Sagaing region (စစ်ကိုင်းတိုင်းဒေသကြီး), followed by Kayin state (ကရင်ပြည်နယ်), Kachin state (ကချင်ပြည်နယ်) and Chin state (ချင်းပြည်နယ်) – all areas of notably active local defence forces.

Figure: Pie chart showing the geographic split of AWIs (count and proportion) established by Myanmar Witness. Graph created with Google Sheets.

On at least three occasions, the Myanmar military have breached the airspace of neighbouring countries, and on two occasions airstrikes impacted the territorial sovereignty of India and Bangladesh.

This investigation reveals that the Myanmar military is heavily reliant upon aircraft manufactured abroad – namely Russian or Chinese air assets – for its almost daily attacks. The Russian-manufactured Mi-35 was the most sighted aircraft within reports of airstrikes collected by Myanmar Witness.

Figure: Helicopter alleged to be from the Taung Kalay village attack. The helicopter has been identified as a Mi-35, and can be seen firing (Source: Facebook).

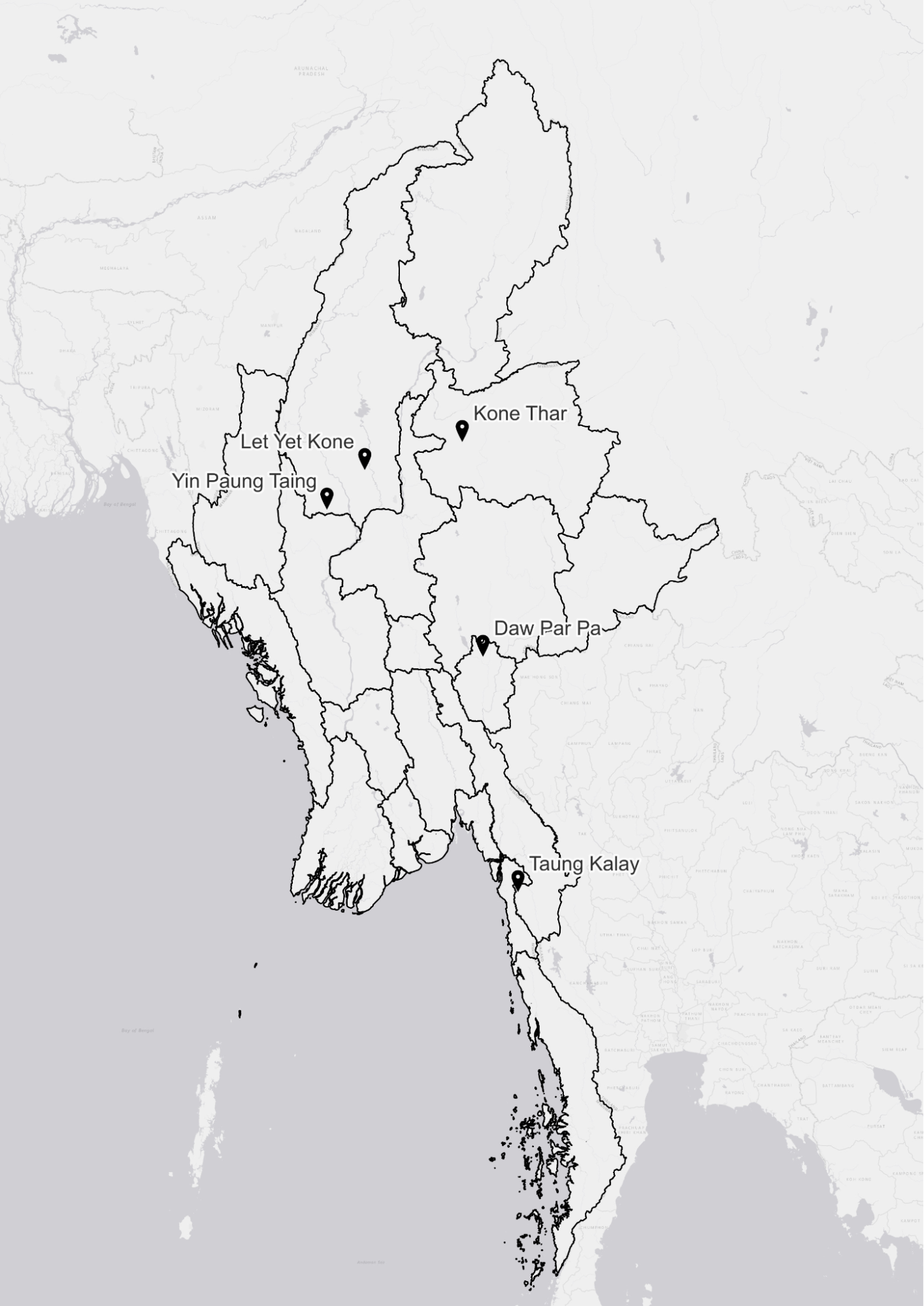

This report builds upon the conducted quantitative study through an exploration of five emblematic case studies of AWIs across Myanmar. Myanmar Witness has identified, verified, analysed and reported on these incidents in an attempt to reveal the human impact of these airstrikes.

The strikes conducted by the Myanmar military as part of their airwar campaign have hit schools, medical facilities, sites of religious significance, and, in all of the case studies included here, civilian homes and infrastructure.

Figure: Geolocation image of Daw Parpa village, highlighting the destroyed clinic area – with red roofing – and residential buildings (source: private).

Figure: Geolocation of a damaged school building in Let Yet Kone village.

The case studies occurred in the following locations, on the date ranges included:

Yinmarbin Township, Sagaing – 11 August 2022

Loikaw Township, Kayah – 9 August 2022

Tabayin Township, Sagaing – 16 September 2022

Kyaikmaraw Township, Mon State – 12 November 2022

Namhsan Township, Shan State – 7 to 11 December 2022

Figure: Location of the case studies explored in this report. Map created with QGIS.

In the case studies explored, both a preemptive (proactive) and a retaliatory (reactive) aspect to the Myanmar military’s conduct has been identified. Proactive strikes, largely targeting hard to reach areas, continue to focus on areas with EAO control (such as Camp Victoria). On the other hand, reactive strikes, accompanied by ground troop offensives (often in parallel with the use of fire), appear to target areas of active conflict with PDF and EAOs.

Figure: [Top] Video footage demonstrates two helicopters in the area of Kone Thar, alleged to be from the day Kone Thar was attacked. This video footage has not been found in an earlier iteration online by Myanmar Witness. (Source: Private). [Bottom] Video footage that appears to show Kone Thar having been attacked; the video is from, or close to, the same location of the footage of two helicopters in the area. (Source: People’s Spring).

The Myanmar military’s domination of the sky also serves as a method of intimidation and fear, particularly when facing an opponent with limited to no air response capability.

Myanmar Witness views the conduct of airstrikes and the use of intentionally lit fires as two-tactical-sides of the same strategic coin. Although these two tactics are separate, they both serve to quell opposition and thus, serve a greater strategic goal. The intentional use of fire will be the subject of a forthcoming report by Myanmar Witness.

Figure: [Top] Image of a fire in Yin Paung Taing village, geolocated to: 22.071472, 94.791664. [Bottom] UGC collected and analysed by Myanmar Witness that demonstrates damage to civilian infrastructure and pagodas (source: Myanmar Now and မြေလတ်အသံ – Myaelatt Athan).

This report emphasises the prevalence of airstrikes in Myanmar and seeks to shed light on those who are responsible so that they can be held to account for all related atrocities.

To read the full report, download the PDF.

Warning: This report contains graphic content.