Executive Summary

Between September 2021 and May 2022 Myanmar Witness has verified almost 200 fires that have been reported to have occurred as part of arson attacks on civilian communities in Myanmar, affecting homes, buildings and livelihoods.

Some of the fires can be attributed to the Myanmar security forces and pro-military groups through either direct or indirect evidence. In a number of the cases, while the fire was the initial indicator, more evidence was identified providing further details on the context of the events, including killings, executions, forced displacement and detentions. Some of these will be covered by a forthcoming Myanmar Witness report on retaliation against communities in the north-west of Myanmar.

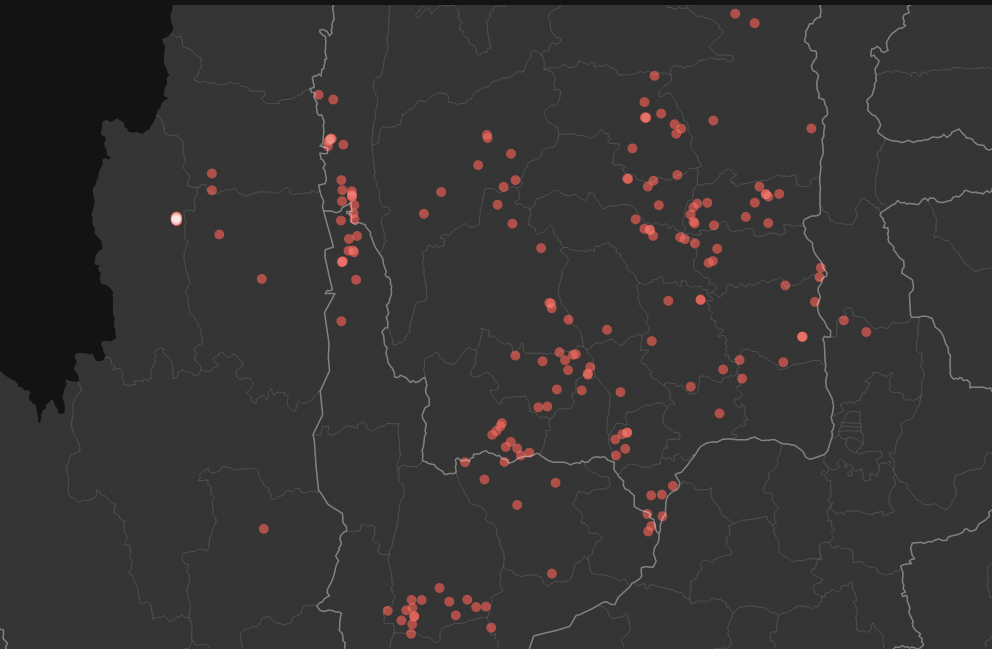

While there were attacks identified on communities between September and December 2021, this rapidly increased in the beginning of 2022 with at least 40 attacks occurring in January and February alone, followed by at least 66 attacks in March and April and 40 in May 2022.

In 2021, fires were focused along the river joining the Sagaing and Magway region as clashes intensified in the low-lying areas. In 2022 Myanmar Witness verified a significant trend of fires happening specifically in Magway’s Pauk Township and Sagaing’s Pale, Yinmarbin, Shwebo and Taze Townships. These trends reflected broader conflict dynamics and the locations of clashes between People’s Defence Forces (PDFs), ethnic armed organisations (EAOs) and the Myanmar military.

There have been numerous reports of the deliberate mass burning of buildings, including essential civilian infrastructure and protected buildings such as churches, by the security forces, allegedly in retaliation for community support to PDFs and the National Unity Government (NUG). Myanmar Witness has verified five incidents of large-scale, systematic destruction by fire in communities reported to be linked to anti-military and pro-democracy activity. While it was not possible to attribute these fires to the Myanmar military (who continue to claim that PDF forces are setting fire to their own communities), footage verified by Myanmar Witness is consistent with the dates and locations reported by local media and residents, who claim that the military were responsible.

EDITORS NOTE: Between completion of analysis and publication, Myanmar Witness verified a further 19 incidents of fire, bringing the total as of the end of June 2022 to 217 verified fires, with July verification ongoing.

Introduction

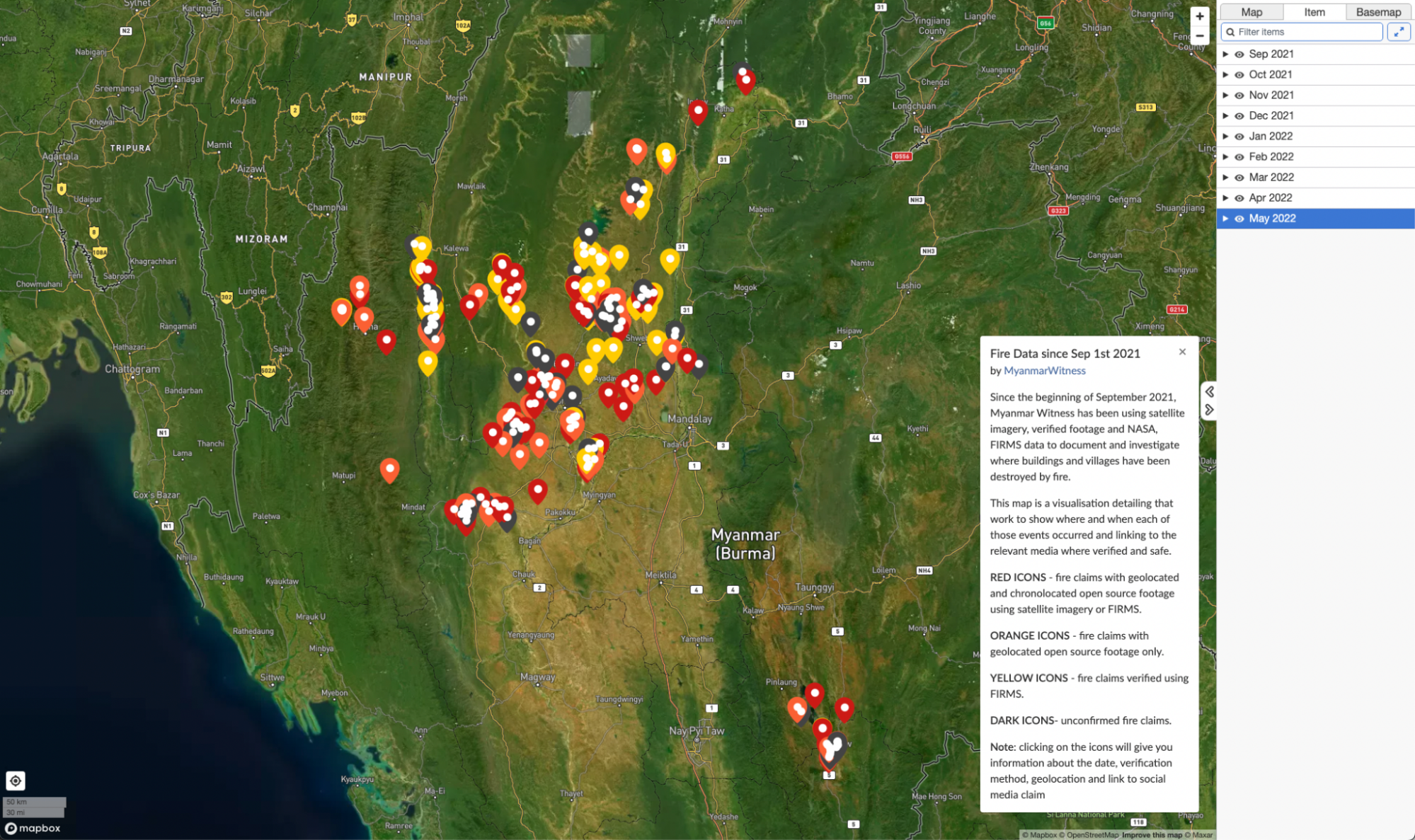

Since the beginning of September 2021, Myanmar Witness has been using satellite imagery, verified footage and NASA Fire Information and Resource Management System (FIRMS) data to document and investigate where buildings and villages have been destroyed by fire.

Myanmar Witness researchers maintain a regularly updated and publicly available map visualising where and when each of those events occurred, and links to relevant content where verified and safe. This can be found here (Figure 1). This report provides analysis on trends and case-studies identified through this mapping effort.

Figure 1: publicly available map of fires documented by Myanmar Witness where villages and buildings have been targeted or destroyed.

Methodology

The incidents seen in this report relate to verification done by Myanmar Witness as part of its effort to collect, preserve, verify and investigate interferences with human rights to a judicial standard. All of the fire-related incident data relied upon in this report has been mapped and made available here.

The process of verification almost always commences with the identification and subsequent exploration of a claim of arson. The claim could either be a news article or social media text, video or photo content, of either a fire in a village, or the destruction of buildings by fire.

In order to check the veracity of these claims, and ensure reliability of evidence, Myanmar Witness investigators followed a stringent process by:

Cross referencing the claim of what village was allegedly destroyed with satellite imagery from that time to see if there are either active fires in the village, or if there are burned buildings

Cross referencing the claim with near-real time NASA FIRMS fire data, which picks up heat signatures on the Earth’s surface

Verifying any attached video or photographic evidence of fires or destroyed buildings through geolocation (cross referencing features in the image with those on satellite imagery) and chronolocation (matching the time of the footage).

At times, a claim was not used to identify the fire, but rather monitoring of available satellite imagery or NASA FIRMS followed by cross-referencing with other sources to check the veracity of that information.

The verification of those incidents is ranked as follows, to be inclusive of data limitations and have transparent verification benchmarks.

Data cut-off for this report was September 2021 to the end of May 2022.

Fire Trends Analysis

Overview

Myanmar Witness has verified, through a combination of geolocated footage, satellite imagery and FIRMS (red, orange and yellow data according to the code above) 196 fires reported to have occurred as part of arson attacks in Myanmar between September 2021 and May 2022, with a further 46 unconfirmed claims.

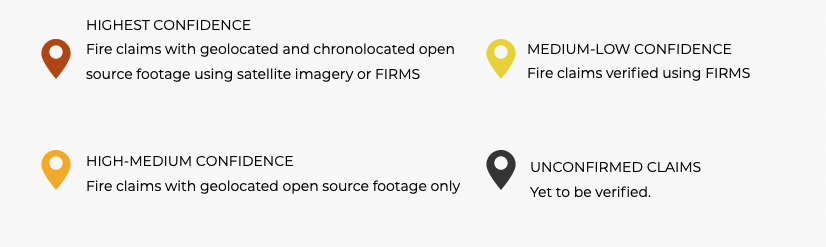

The geographical distribution of these verified fires in Myanmar’s north is illustrated in Figure 2 below, showing a concentration of events in Sagaing and Magway. The chronological distribution of these verified fires is illustrated in Figure 3, showing a rapid increase in verified events from January 2022.

Figure 2: Myanmar Witness verified incidents where fire has been used against villages and towns since September 2021.

Figure 3: Myanmar Witness verified incidents where fire has been used against villages and towns from September 2021 to May 2022. Full graphic available here.

Fires documented in late 2021

While most of this report relates to incidents in 2022, events in 2021 indicate a potential shift in regional focus by the Myanmar military in its strategy to oppose local groups in the country’s north. There were two main areas where fires were concentrated in Myanmar’s north, and that intensified toward the end of 2021. These are seen in the map below (Figure 4), with Sagaing and Magway region on the left side (close to the Chin State mountains), and Sagaing’s eastern region on the right.

Figure 4: Map showing concentration of fires recorded by Myanmar Witness in 2021. Colour coding of icons corresponds to the level of verification as set out in the methodology. Polygons indicates average area of activity

Fires documented in 2022

From the beginning of 2022, Myanmar Witness identified new focus areas for fire-related incidents. While 2021 appeared to focus on two specific areas, the regions in 2022 appeared to ‘fill the gaps’ and expand outwards from those concentration areas.

Figure 5 shows the areas in red, which were the areas documented in 2021, compared with areas in yellow, which were the focus areas of fire-related incidents in 2022.

Figure 5: Map showing concentration of fires recorded by Myanmar Witness in 2022. Colour coding of icons corresponds to the level of verification as set out in the methodology. Polygons indicate average area of activity – red indicates 2021 areas, yellow indicates 2022 areas.

These areas were also where there was significant intensity of fighting within those regions, as documented by media reports and in Myanmar Witness’ forthcoming TimeMap of conflict-related incidents (Figure 6).

Figure 6: TimeMap showing incidences of conflict-related footage verified by Myanmar Witness

Case-Studies

The incidents verified by Myanmar Witness vary in type, as well as size and effort of attack. However, there have been multiple reports of the wholesale and systematic destruction of communities by military forces, allegedly in retaliation for support to the PDF and the NUG. Myanmar Witness has verified four incidents of large-scale destruction by fires in communities reported to be linked to anti-military activity. While it was not possible to attribute these fires to the Myanmar military (who continue to claim that PDF forces are setting fire to their own communities), footage verified by Myanmar Witness is consistent with the dates and locations reported by local media and residents, who claim that the military were responsible.

A Shay See village, Sagaing, 1 May 2022

In A Shay See village in the Kale area of Sagaing on 1 May 2022, local residents alleged that the village was targeted by the Myanmar military in retaliation for a previous attack by local PDF forces where members of the Myanmar security forces were injured. Security forces allegedly looted houses before burning them down.

In that case, almost all of the village (location: 22.849929, 94.074752) was destroyed in what appeared to be a systematic effort to burn down a significant portion of the village’s buildings. Drone footage obtained by Myanmar Witness showed the aftermath of the village and the scale of destruction. MW created a panorama of that footage (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Destruction of buildings by fire in A Shay See village, 1 May 2022

Thantlang Township, Chin State, September 2021 to May 2022

Thantlang has reportedly acted as a key base of resistance to the military coup in Myanmar, and was one of the areas of focus for military Operation Anawrahta in late 2021. Local media and NGOs report that the military was responsible for the widespread destruction of homes in Thantlang. SAC Deputy Information Minister Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun claims that local PDF forces were responsible for burning the homes of their own communities.

Myanmar Witness has verified over 20 separate fires in Thantlang since September 2021 and verified imagery showing over 1,000 destroyed or heavily damaged buildings (Figure 8). Further details on Thantlang will be available in our forthcoming report on attacks against communities in Myanmar’s North-West region.

Figure 8: Map of the total individual visibly destroyed or heavily damaged structures in Thantlang utilising footage from September 2021 – 26 May 2022. There are around 1,015 individual icons in this mapping

Figure 9: Examples of the destruction of buildings in Thantlang verified by Myanmar Witness through cross-referencing with geo-thermal imaging data

Kar Paung Kya, Taze Township, Sagaing, October 2021 to May 2022

Taze Township, and the village of Kar Paung Kya in particular, has been recorded as an active area of resistance to SAC rule, first as the centre of protests against the military coup, and later as an area of military occupation and operation for the People’s Defence Force – KPK. Myanmar Witness has verified four incidents of fire in the village between October 2021 and May 2022. Analysis of satellite imagery shows that at least 105 structures have been heavily damaged or destroyed by fire (Figure 10).

According to local media and residents, the military was responsible for the fires in Kay Paung Kya. Pro-military media claim that PDFs were responsible for attacks in the village and that they burnt their own homes. Myanmar Witness was not able to verify claims of responsibility for the fires.

Figure 10: Structure damage in Kar Paung Kya village, Taze since December 2021. The red symbols indicate burned while the yellow indicates damaged structures. Satellite imagery from Google Earth.

Tha Pyay Aye, Yinbarbin, Sagaing 28 February 2022

A similar effort to clear out a large portion of a town was seen on 28 February 2022, when at least 45 structures were destroyed in Tha Pyay Aye in Yinmarbin (22.20029068, 94.87830353). Local media reported that military forces robbed and burnt the village in retaliation for alleged PDF activity in the area. Figure 11 shows verification of images which Myanmar Witness used to document this incident.

Figure 11: Images of fire and verification of structure damage in Tha Pyay Aye. Red icons indicate burnt buildings

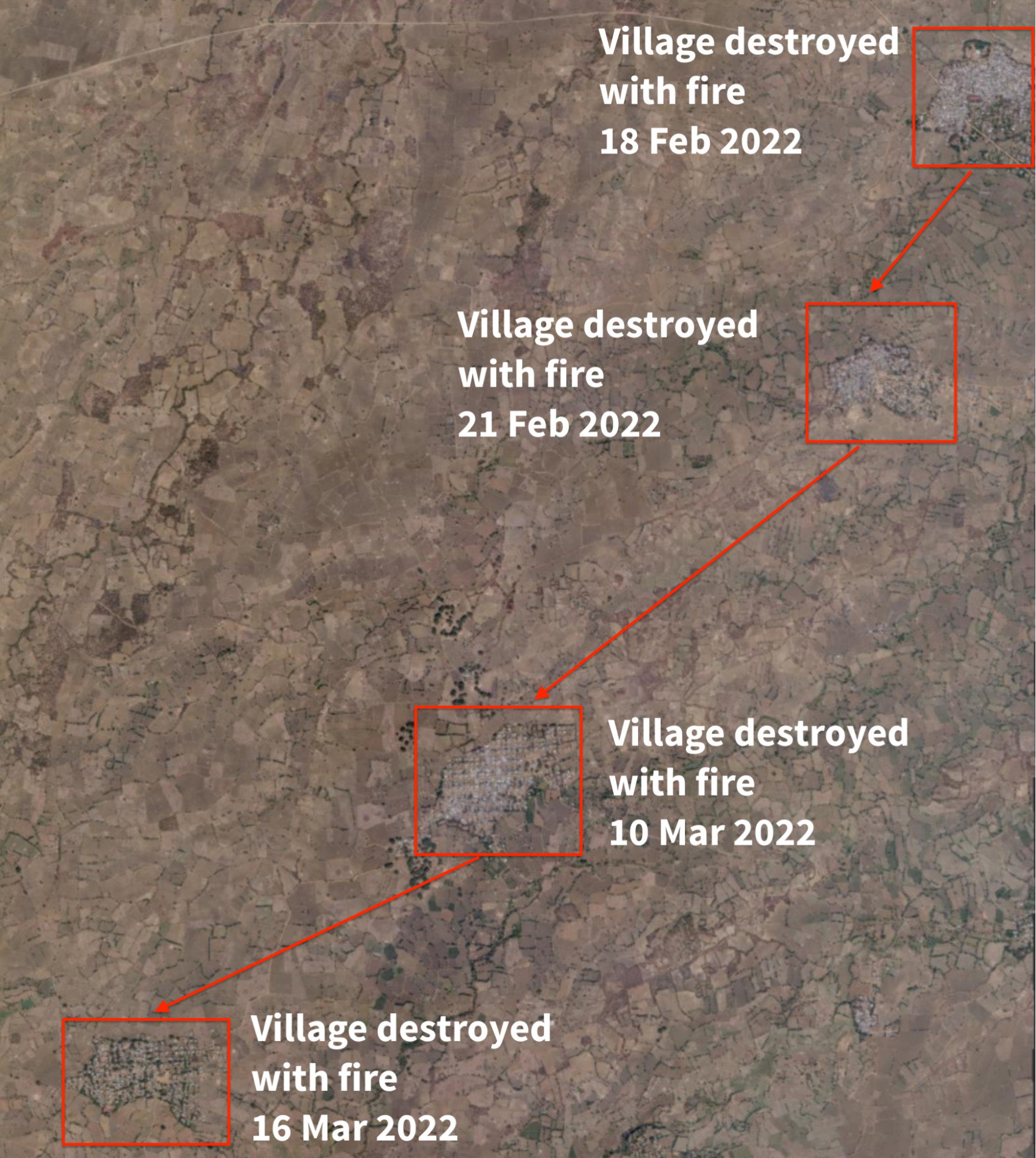

‘The Domino Effect’: Chaung U, Pale, Sagaing 18 February 2022

Whole-village destruction was also witnessed in Sagaing between 18 February and 16 March 2022 around Chaung U village, located here: 21.97357941, 94.72136688. This destruction also saw consecutive villages targeted in the surrounding area.

MW analysts identified the fire damage first through NASA FIRMS, as seen here which indicates heat signatures at about 1900 on 18 February 2022. Satellite imagery obtained from Planet dated 20 February 2022 shows almost the entire village has been destroyed, with clear signs of ash remaining from the fire damage, as seen in Figure 12.

Figure 12: Fire damage to Chaung U village visible on 20 February 2022

In the days after, a village a few kilometres south located at 21.96233, 94.71564, was destroyed, and then subsequently a village located at 21.94477, 94.70029 in what appears to be a domino effect of village attacks and destruction (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Shows the four villages targeted in chronological order, as seen on Planet imagery from 12 March 2022. Note, the village targeted on 16 March 2022 is not seen as destroyed in this satellite image, which was taken four days before, however more recent imagery has been used to verify the town’s targeting. This chronological destruction does not indicate responsibility by the same unit, rather the linear timeline of destruction.

Let Yet Ma, Myaing Township, Magway, 14 May 2022

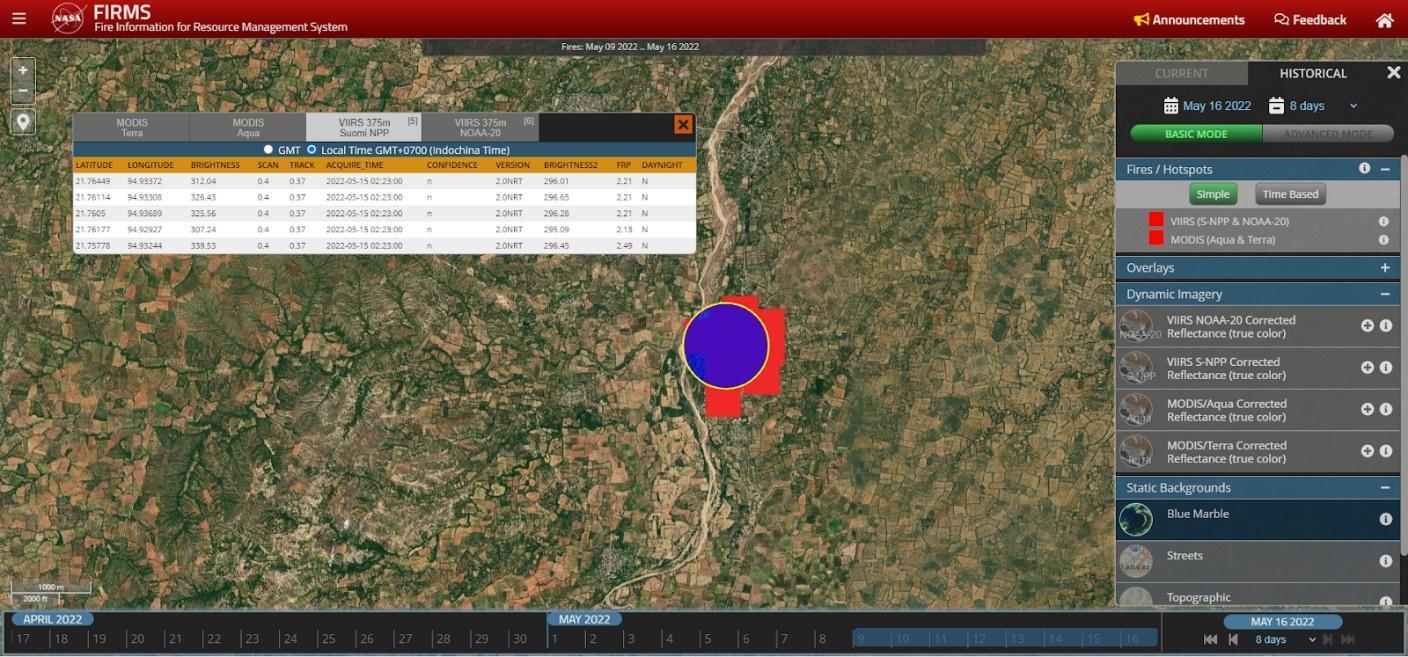

According to local residents interviewed by Burmese media and multiple social media posts, forces aligned to the State Administration Council (SAC) set fire to multiple homes in Let Yet Ma village (coordinates 21.758579, 94.934137) on the afternoon of 14 May 2022. The attack reportedly followed recent fighting between SAC forces and the local PDF near the village.

While the scale of the destruction meant it was not possible to verify images reportedly showing the burnt structures (posted here by Khit Thit Media), NASA FIRMS fire data shows extensive fire events in the village on the 14 May 2022 (Figure 14), and remote sensing shows the scale of the damage to the village (Figure 15).

Figure 14: FIRMS data showing heat signatures of fires in Let Yet Ma village on 14 May 2022

Figure 15: Remote sensing analysis of fire damage in Let Yet Ma. Dark areas indicate burnt buildings

Use of fire by the Tatmadaw in Myanmar’s internal conflicts: A historical perspective

The use of fire as a weapon by the Myanmar military has historical significance. In research conducted by another organisation affiliated with Myanmar Witness, the Ocelli Project, the systematic use of fire was mapped using satellite imagery. This showed that of the 38,705 buildings destroyed in Rakhine State between 2016 and 2020, more than 24,000 of those demonstrated clear signs on satellite imagery that they were destroyed by fire. Many of those villages were targeted in specific ‘waves’ and were concentrated around specific dates.

Figure 16: Burned villages mapped in Rakhine State between 2016 and 2020.

The analysis also showed that despite the widespread targeting of villages in Rakhine State, villages were discriminated between those that were of Muslim faith, associated with Royinga groups, and those that were majority Buddhist villages. The majority of those villages that were associated with Rohingya populations were targeted, while the Buddhist majority villages were not. (Figure 19)

Figure 19: The village on Nwar Yon Taung (20.864660, 92.388359) in Maungdaw region was destroyed, while next to it, other buildings and communities remain untouched. A number of other villages were identified like this in the research where communities with Buddhist shrines were left untouched during the Tatmadaw’s burning of communities in Rakhine.

List of Abbreviations

Ethnic Armed Organisations – EAOs

Fire Information and Resource Management System – FIRMS

National Unity Government – NUG

People’s Defence Forces – PDFs

State Administration Council – SAC