On 24 December 2021, 35 people were killed and their bodies burnt near a village called Moso, located in Myanmar’s Kayah state.

While state media blamed the fire on local resistance forces, open source evidence points to military involvement in incidents described by the UN as having “all the hallmarks of a war crime”.

Two years on, a report released today by CIR’s Myanmar Witness project reveals how such incidents have become routine and commonplace in a conflict where the military has often weaponised fire to spread fear and control the population.

Investigators collected details of 146 incidents between March 2022 and September 2023 in which more than 440 bodies were burnt, according to local media reports and user-generated content.

Matt Lawrence, Director of the Myanmar Witness project, described the incidents as “another horrific dimension to the impact of the conflict on the people of Myanmar.”

Photos and videos collected from social media sites such as Facebook and X allowed the team to identify the burnt bodies of 150 victims, with some images showing what appear to be the charred bodies of children or victims’ bodies stacked on top of one another before being set alight.

Who these individuals were, and how they ended up here, is far less clear, but open source evidence suggests that some were burnt alive, while others were burnt after death or as a result of an artillery or air strike.

Several cases included reports of sexual violence – including claims that women had been raped and burnt alive – indicating the indiscriminate nature of the conflict, where women and children are often caught up in the violence.

The report suggests these incidents could be part of an attempt to control populations through “fear of improper burial or death”, as graphic bodily disfigurement or lack of identifiable remains would likely prevent open-casket funerals or religious cremations from taking place.

“Many bodies are unrecognisable after being burnt in this way, leaving the families of victims with horrific memories of their loved ones and making it difficult to properly bury them,” Lawrence said.

Despite the overwhelming weight of reports claiming the Myanmar military was responsible, conclusive evidence was hard to find. It’s possible this is a result of self-censorship among family members or witnesses, which limits visual evidence from surfacing, as well as incidents being carried out surreptitiously.

There are some indications of military involvement, however – such as the geographical trends mapped out in the report, explains Lawrence.

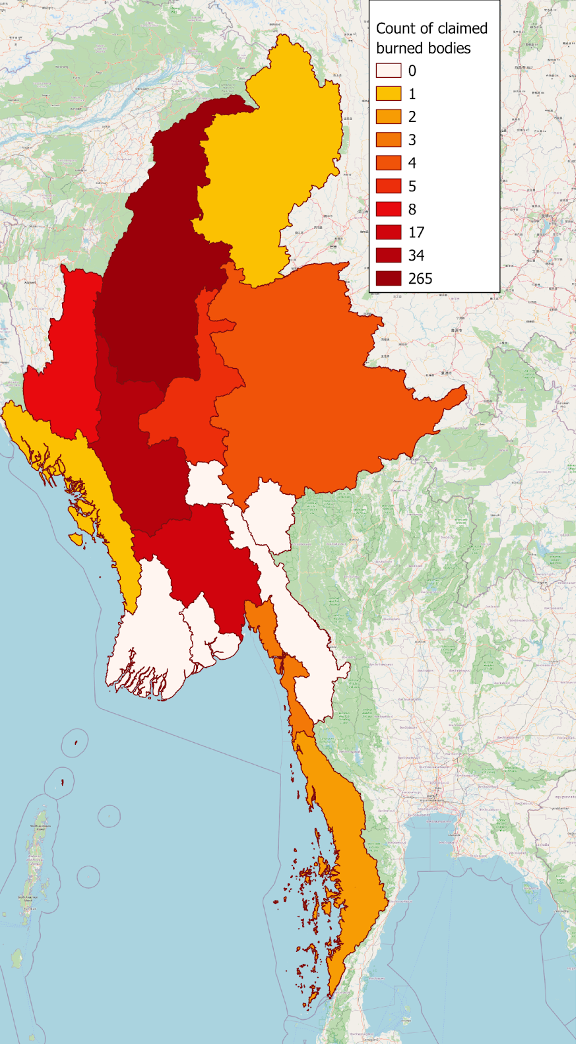

“Reported incidents of bodies being mutilated by fire and people being burnt alive are most prevalent where the armed resistance is strongest, suggesting that this is deliberate and systematic retaliation by the military against the population.”

Investigators found that three-quarters of the images of the burnt bodies linked them to Sagaing, often considered the violent epicentre of Myanmar’s conflict and the backdrop to numerous arson attacks, airstrikes and beheadings.

In the claims collected by Myanmar Witness, the majority of victims were located in Sagaing and Magway.

In the claims collected by Myanmar Witness, the majority of victims were located in Sagaing and Magway.

Sagaing has been the setting of violent mass killings, such as an incident that took place in May 2022, when soldiers executed 27 villagers and then burnt their bodies.

In this incident, Myanmar Witness investigators were able to prove a “definitive link” between the Myanmar military and the executions, with soldiers pictured alongside victims whose throats had been slit. Insignia on the soldier’s uniforms and weapons allowed investigators to trace the specific regiment they belonged to.

The burning of villages and use of scorched earth techniques were seen in Myanmar prior to the February 2021 coup, including during theRohingya genocide in Rakhine state and the 2011 Kachin conflicts. However, since the 2021 coup, the use of fire appears to have intensified.

Using satellite imagery, verified social media footage and NASA FIRMS data, Myanmar Witness has documented and mapped hundreds of villages set alight since February 2021. Fire has also been used to target food infrastructure, including storage facilities and livestock – a potential breach of the Geneva Conventions, which considers such facilities indispensable to the survival of the local population.

While military involvement is often impossible to determine from open source, reports are most common in areas where the People’s Defence Force and resistance activity are highest, suggesting fire is a key part of military strategy in areas of known resistance.

Today’s report, released two years after horrific events in Moso, reveals how Myanmar’s villages continue to burn, and civilians are often caught up in the violence.

With press freedom severely restricted in the country, and the few remaining outlets forced to adhere to the military’s version of events, photographs and videos uploaded to social media provide a rare glimpse of the scale of violence civilians are exposed to daily.

This content is often upsetting and disturbing to see, but open source analysis plays a critical role in laying bare atrocities that would otherwise go unreported – allowing the world’s attention to stay on Myanmar.

Read Mynamar Witness’s full report, ‘Stories left behind in the ashes’,