Uncovered: The devastating impact of Myanmar’s rare earth mining boom

6 min read

Myanmar Witness

Expansion of road networks from what appears to be a former active mining site to a new one [25.663465, 98.287823]. Image: © 2024 Planet Labs Inc. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission

Demand for rare earth minerals has surged in the last two decades – a result of the global transition towards greener technologies and increasing reliance on mobile phones. But what if we told you that the rare earth mining operations behind these technologies – used in wind turbines, electric vehicles and the smartphone you carry in your pocket – were having potentially devastating consequences for Myanmar’s people and environment?

Using open source techniques, CIR’s Myanmar Witness project has uncovered the hidden costs of Myanmar’s rapid expansion of rare earth mining. The impacts are two-fold: deforestation, soil degradation, and water pollution, which not only harm the natural landscape but also lead to livelihood losses, poor sanitary health, and potential displacement among local communities.

Surging demand

Rare earth minerals are a group of 17 chemically similar elements with powerful magnetic, luminescent, electrical, and catalytic properties. They are needed for electronics like smartphones and electric vehicles, renewable energy technologies like wind turbines, and for defence mechanisms such as radar and sonar systems. Some industrial wind turbines require nearly a tonne of rare earth minerals, so increasing reliance on renewable energy technologies means demand for rare earth minerals has surged in recent years. Demand for smartphones and other technology using rare earth minerals is also growing, increasing demand further.

However, only a handful of countries dominate the production of rare earth minerals, including China, the US, Myanmar, and Australia, resulting in significant expansions in rare earth mining in these countries.

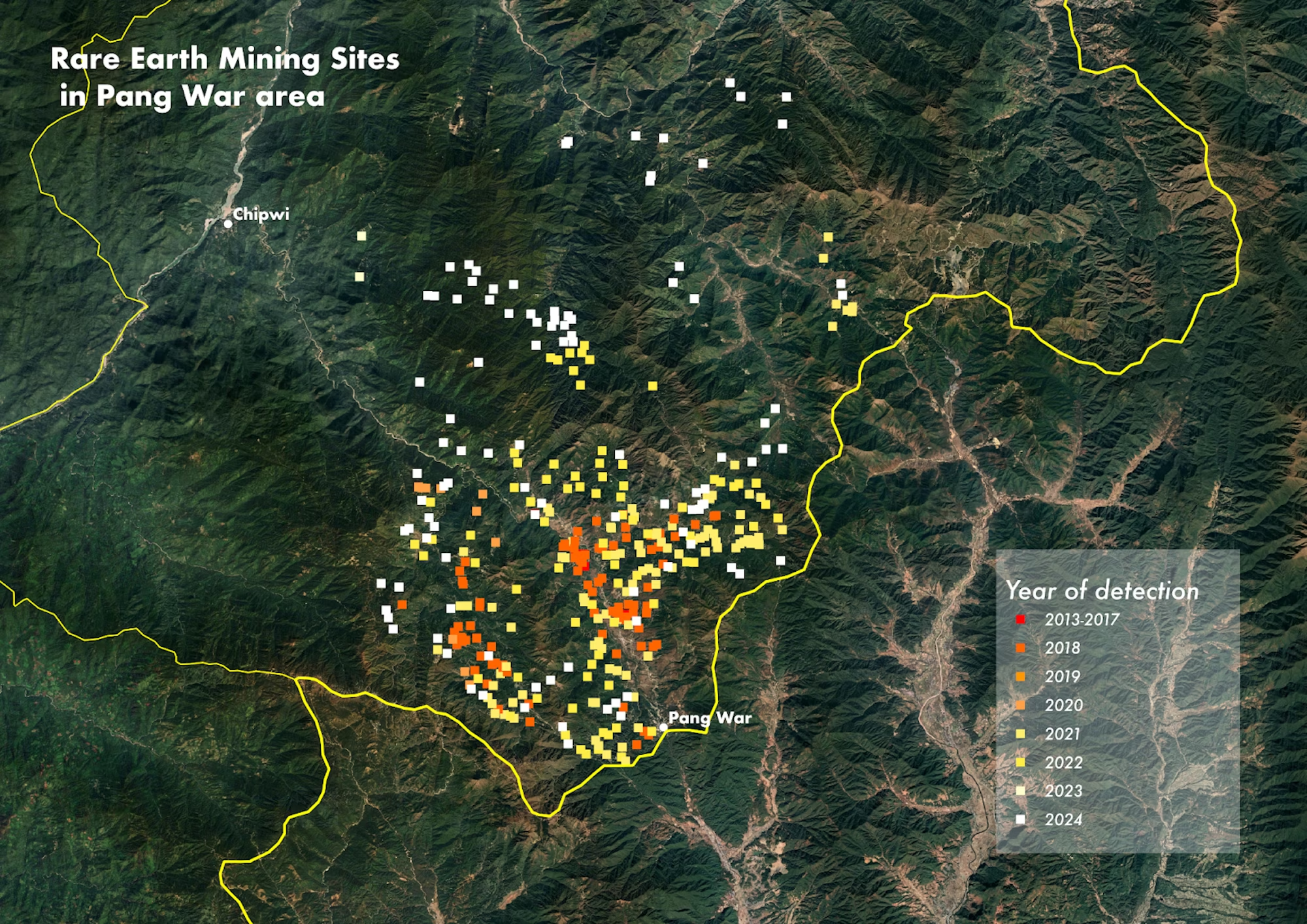

By the end of 2024, Myanmar Witness identified nearly 400* rare earth mining sites across Kachin State using open source techniques. To assess the social and environmental impacts of these sites, Myanmar Witness focused on the Pang War region, in Chipwi township in Kachin State and some of its surrounding areas. Located in the country’s mountainous northeast, along the Myanmar-China border, Pang War is known as a significant rare earth mining location.

Latest reports, direct to your inbox

Be the first to know when we release new reports - subscribe below for instant notifications.

Open source analysis reveals how rare earth mining sites emerged and expanded in Pang War between 2013 and 2024. Map: Google Earth © CNES/Airbus; boundaries: Myanmar Information Management Unit; data: Myanmar Witness

A rapid mining expansion

Open source techniques provide a unique lens into the expansion of rare earth mining in Pang War, as reporting from the ground is difficult due to restricted access to the mines and ongoing violence since the 2021 coup.

Myanmar Witness assessed the growth in rare earth mining in Pang War by analysing satellite imagery and user-generated content (UGC) of sites and operations. To understand the social impact of mining, analysts monitored reports of protests, displacement and loss of livelihoods on social media channels and in online media.

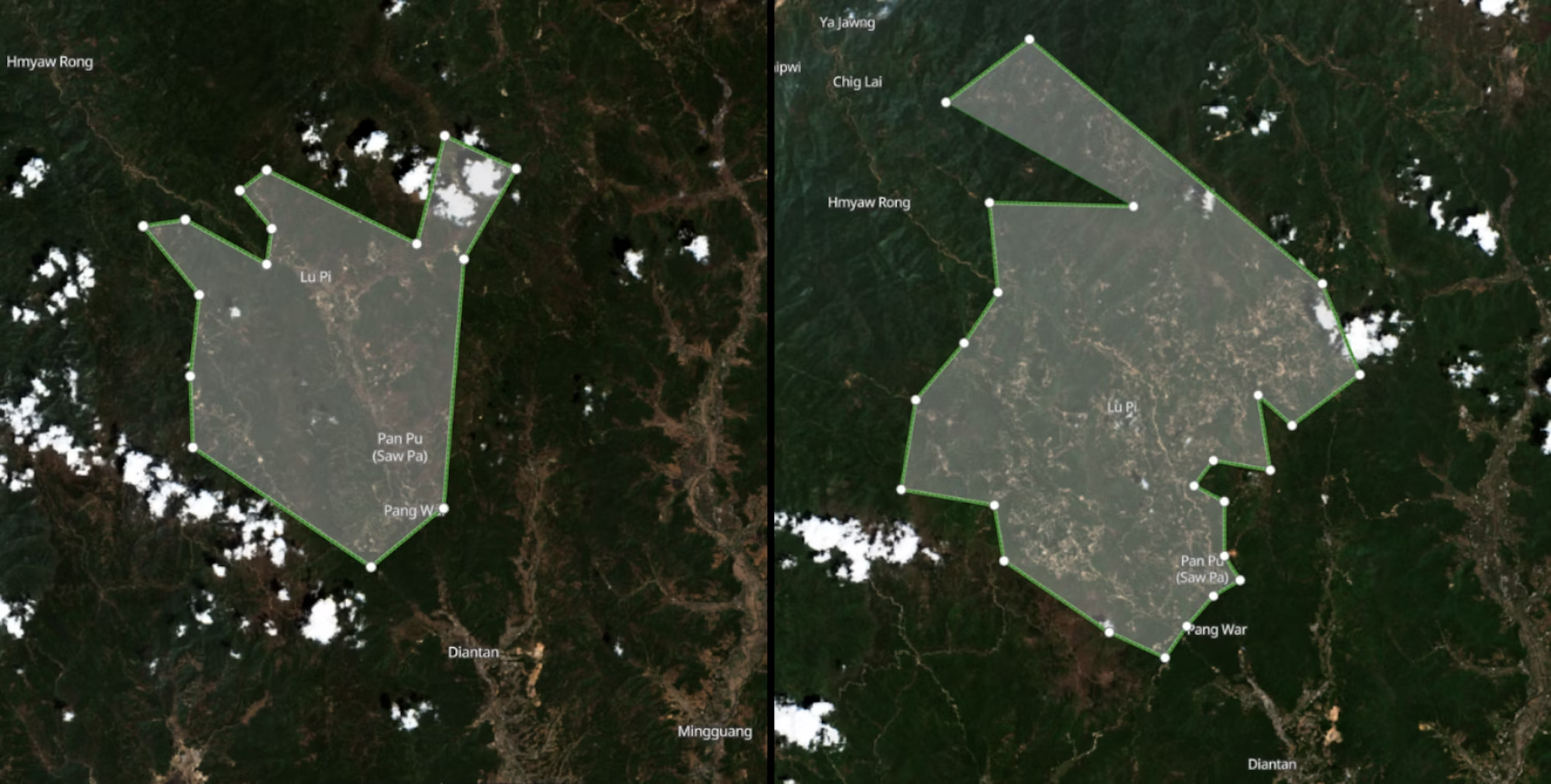

Myanmar Witness used Sentinel Hub’s area measurement tool to analyse the expansion of rare earth mining activities in the area. Analysis reveals that Pang War has seen a rapid expansion of rare earth mining in recent years, with mining sites doubling from 260km² to 467km² between 2018 and 2024.

Left: Satellite imagery of Pang War on 3 April 2018 [25.603095, 98.377333] showed fewer rare earth mining sites and relatively intact vegetation. Right: By 3 April 2024, the mining area had increased to 467 km². Images: Modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2018 & 2024/Sentinel Hub

The satellite imagery below reveals how mining operations in the area have grown in the space of a year. Changes include the development of water pools and pits essential for the extraction of rare earth minerals (shown in the white circles), the emergence of potential new mining sites (yellow boxes), and ground colour changes which suggest deforestation – a process commonly associated with rare earth mining (blue boxes).

Satellite imagery of the Pang War area shows significant developments between 7 April 2023 [left] and 25 April 2024 [right], including new water pools, new mining areas and ground colour changes. Images: Modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2023 & 2024/Sentinel Hub

Mining has carved up Pang War’s landscapes

Additional high-resolution satellite images show how previously untouched areas transformed into mining sites in the Pang War area. As shown below, what were green landscapes in 2021 now feature cleared land, the rectangular and circular pools characteristic of rare earth mining operations, and expanded road networks built to provide access to mining sites and facilitate increased traffic.

Left: Satellite image of the Pang War area on 19 March 2021, showing a rural area with one observed road. Google Earth © 2024, CNES/Airbus. Right: By 13 February 2024 the area had transformed into a mining site, with several roads visible. Image © 2024 Planet Labs Inc. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission

Widespread deforestation

By analysing satellite imagery against tree cover loss data, Myanmar Witness found that large areas of vegetation have been cleared, likely to facilitate Myanmar’s growth in rare earth mining sites. The findings are stark: Myanmar’s Chipwi township, which is roughly the size of Cornwall, UK, lost the equivalent of 10,822 football fields (7.73 hectares) of tree cover between 2018 and 2023, approximately 2.7% of Chipwi’s total forest area.

Based on open source analysis alone, Myanmar Witness cannot definitively confirm that these changes are solely down to mining. However, mining has often been highlighted as a key cause of deforestation, as vegetation is cleared to access mineral and metal deposits and make way for new infrastructure.

The impact of deforestation is devastating: it destroys ecosystems, leading to habitat loss and biodiversity decline. Forest loss and damage also release carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, accounting for around 10% of global warming.

Deforestation and land excavation can also lead to land instability and landslides, particularly during the rainy season when the soil is softer. Myanmar Witness observed these impacts from the expansion of the mining sites in Pang War, with increased landslides and altered mountain landscapes from May to July 2024 (rainy season), which reportedly caused over a dozen injuries and around 50 deaths. As well as being dangerous, soil degradation causes severe erosion which can reduce agricultural productivity and damage critical infrastructure like roads and bridges.

Images from a Facebook post showing Pang War’s road and transportation conditions on 5 July 2024. Image sources redacted due to privacy concerns

Flooding and water safety

Using Sentinel Hub satellite imagery to measure the scale of flooding events, Myanmar Witness found that flooding around the Irrawaddy River – the country’s most important commercial waterway – almost tripled between 2019 and 2024. While the precise cause is unknown, it is possible that this sudden increase could also have been a consequence of environmental degradation caused by deforestation in Pang War. Myanmar Witness could not verify the precise connection between the mining activities and flooding events, but the rapid expansion of mining sites, in line with the frequent occurrence of these natural events, could suggest a potential correlation.

A comparison of satellite images from 17 July 2019 [left] and 3 July 2024 [right]. Images: Modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2019 & 2024/Sentinel Hub

Mining activities can also contaminate local water sources with toxic chemicals, affecting ecosystems and sanitary health. Kachin-based news outlets have reported that Pang War’s drinking water has allegedly been affected by chemical waste from mining activities, meaning local residents cannot drink the water from the streams found along the road to Pang War.

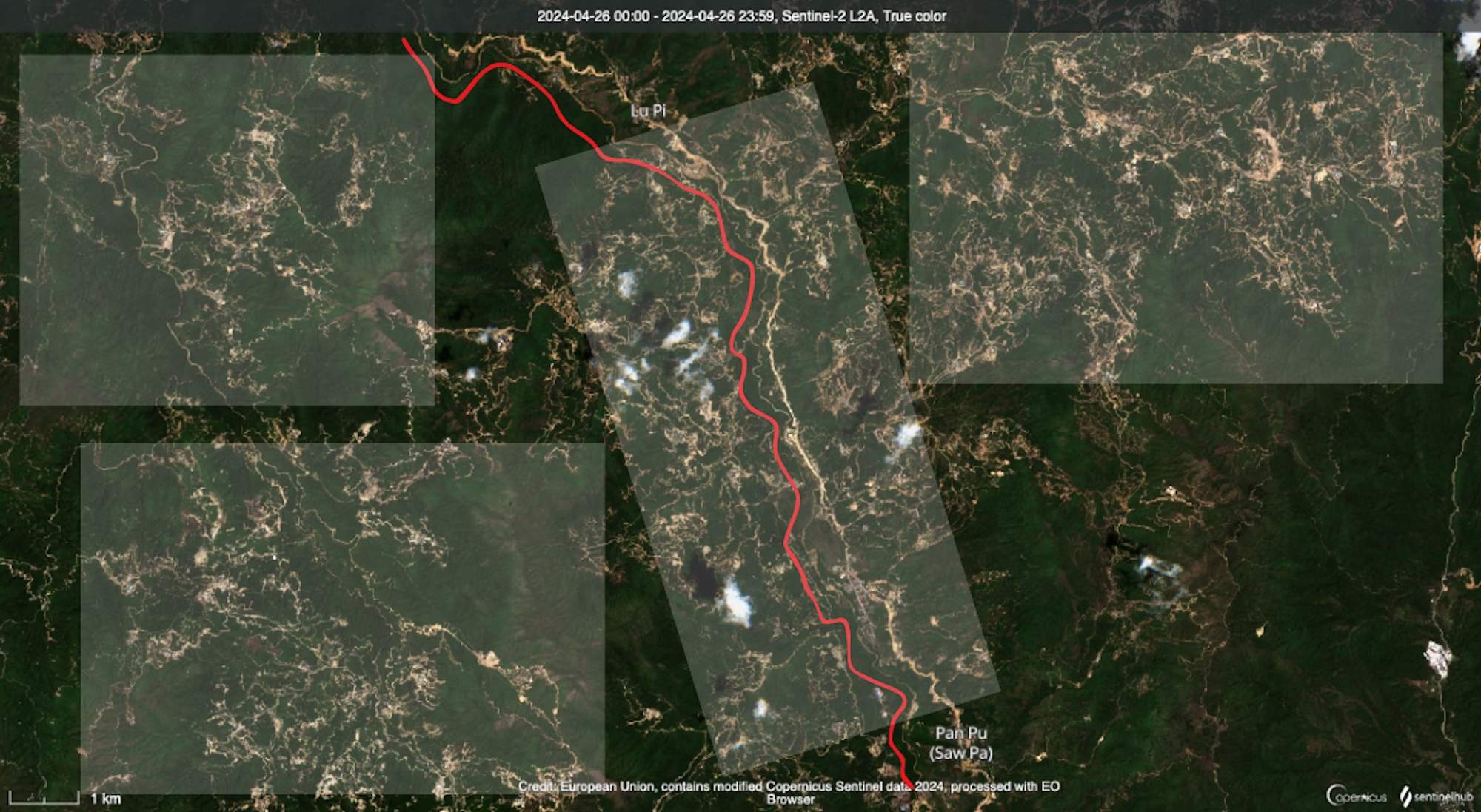

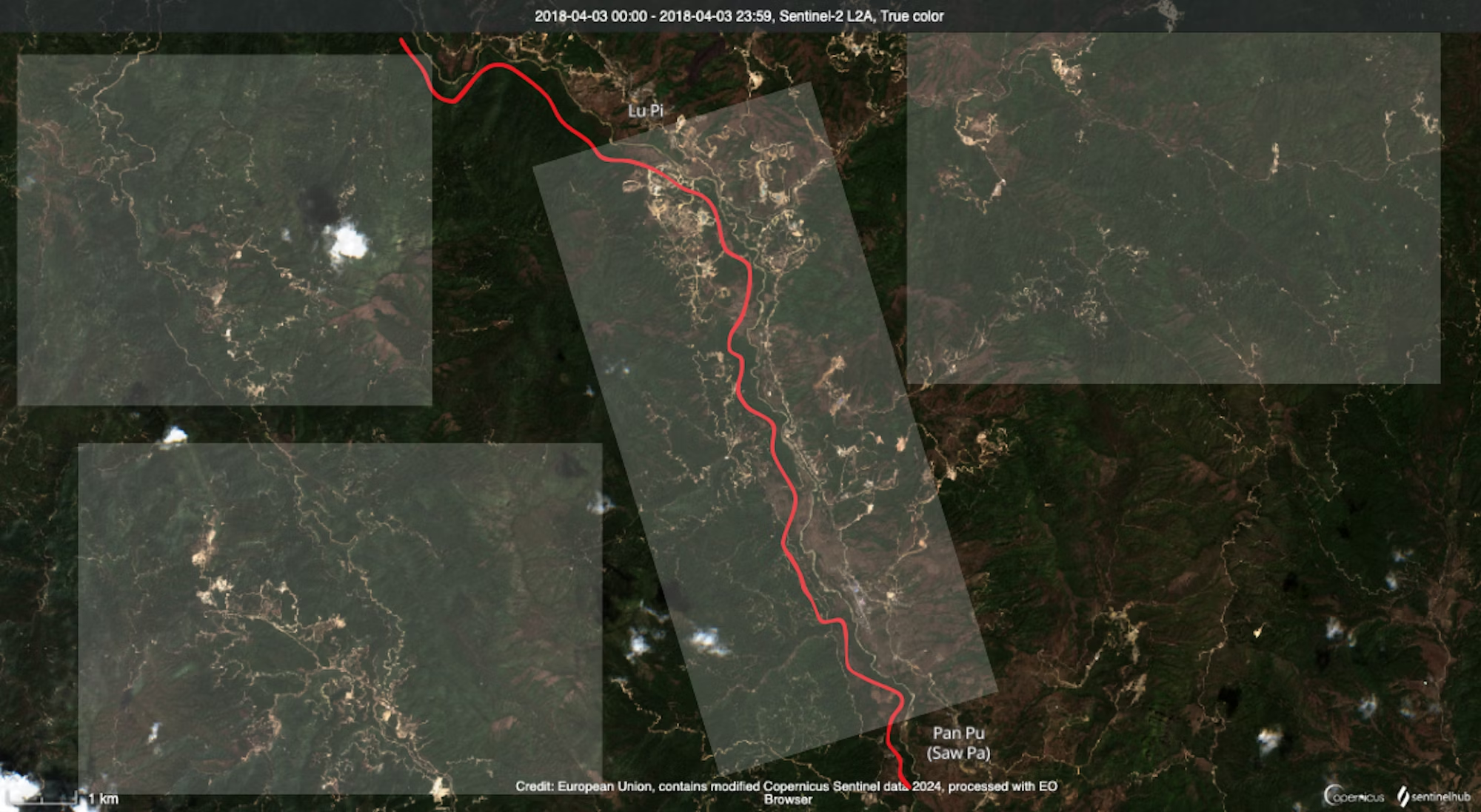

Myanmar Witness could not verify the evidence of waste disposal into the river and prove contamination of the water supply through open source analysis, but found that mining activity has expanded significantly around vital water sources in the Chipwi township between 2018 and 2024, which indicates increased risks of contamination.

Satellite imagery from 2018 [left] and 2024 [right] shows activity around a water source (marked in red) in Chipwi township. Growth around this rural location shows large expansion, highlighted in the grey boxes. Images: Modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2018 & 2024/Sentinel Hub

Disruptive social impacts

As well as severe environmental degradation, mining in Pang War poses significant risks to local communities. Human rights abuses and poor health and safety conditions have been reported at the mines, with the involvement of armed groups like the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) allegedly escalating tensions and contributing to local unrest.

There have been regular reports of protests, displacement and livelihood losses. For example, it was claimed that a protest occurred in an area of the Chipwi township on 5 February 2024 in opposition to the KIA’s alleged authority to mine near a river considered vital to the community, with over 50 people reportedly detained following the protest. Myanmar Witness verified that the protest occurred in Hpa Re village by matching the images in the Myitkyina News Journal’s article to Google Earth imagery. Such incidents highlight unrest among the local population over unregulated mining activities in the area.

Left: Image taken from the protest on 5 February 2024 in Hpa Re village [25.777804, 98.450652] via MNJ. Right: Profile of the mountain range, which matches the mountains in the image. Image: Google Earth, © 2025 CNES/Airbus

Myanmar Witness also monitored the four main local community Facebook groups in Pang War to gain insight into the dynamics of mining activities. Numerous posts advertising job vacancies, and operational footage posted in 2024, indicate that operations at the mining sites are still active and are potentially set to expand. This is not surprising, given that demand for rare earth minerals is likely to increase over the next decade in line with rising demand for clean technology.

Open source methods have been critical in exposing the environmental and social impacts of rare earth mining in Myanmar. Such investigative techniques are vital in a region where there are multiple barriers to on-the-ground reporting, and where press freedom is limited. Monitoring by human rights organisations and the open source community will continue to play an important role in pushing for transparency and regulatory measures to protect local communities and the environment from further damage.

*The operational status and precise number of these sites may vary due to limitations in satellite imagery availability.