Cover image: four women protesters, allegedly detained and later freed by the Taliban, left to right: Dr. Zahra Mohammadi, Parwana Ibrahimkhil, Mursal Ayar and Tamana Zaryab Paryani

On February 11 and 12, it was reported that the Taliban had released a number of individuals from detention, including the female activists Parwana Ibrahimki, Mursal Ayar, Zahra Mohammadi and Tamana Paryani, whose disappearances have triggered international news coverage and concern from civil society groups and organisations.

On February 11, online sources reported that Parwana Ibrahimki, Mursal Ayar, and Zahra Mohammadi had been released from prison, following their reported detention by the Taliban in mid-January.

A day later, reports emerged stating that Tamana Paryani and her three sisters had also been released. AW investigators were not able to independently confirm the women’s release.

The Taliban had publicly denied any involvement in the detentions of the female activists – including in an interview with the BBC where they went as far as accusing Paryani of staging the video she filmed of herself to ‘assist with an asylum claim’.

Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid also previously denied any women were being held, but in an interview with AFP, said authorities had the right “to arrest and detain dissidents or those who break the law”.

While there have been no public statements on their release from the women themselves, TOLO news reported that family members had confirmed the reports. According to family members, the women were pressured to not speak of any details of their arrests and detainments. One source suggested that Tamana Paryani was released on parole under the condition that she would no longer engage in any form of political activism.

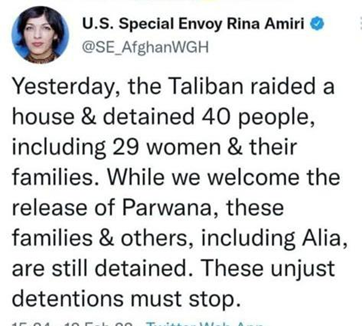

On February 12, Rina Amiri, the US special envoy to Afghanistan, tweeted that following the release of the female activists the Taliban had detained 40 other people, including 29 women and children. The tweet gained widespread traction before being deleted. The Guardian reported that while the tweet was deleted, their sources had confirmed that several women had been detained in Kabul.

Figure: Deleted tweet by US Special Envoy Rina Amiri

Figure: Deleted tweet by US Special Envoy Rina Amiri

In separate developments, on February 11, it was reported that a group of journalists – including two international reporters, one of whom was former BBC correspondent Andrew North – had been released. Taliban spokesperson Zabehullah Mujahid announced that the journalists had been detained for not having the correct documents, but that “they were in good condition” and “in touch with their families”.

The detained journalists were on assignment for the UN refugee agency, who confirmed the group’s release on Twitter.

On Friday, the friends of a British-German former journalist Peter Jouvenal, who was reportedly arrested by the Taliban in December, urged authorities to release him, and said he was being detained ‘in error.’

Since the Taliban swept to power last summer, Afghan journalists have regularly been restricted from reporting. According to Reporters without Borders, at least 50 Afghan reporters and other media professionals have been arrested or detained by the Taliban police or intelligence services since last August.

The same day, it was reported that Musa Shahin, a famous singer from Panjshir, was also released from prison in Herat. He had reportedly disappeared on February 3 while travelling to Iran. Photos emerged on social media of Musa Shahin covered in lash marks upon release.

The recent detentions have once again raised questions around the future of women, campaigners and journalists in Afghanistan. After taking charge of Kabul last August, the Taliban promised women’s rights, media freedom, and amnesty for government officials.

International organisations such as the UN have raised concerns over what they describe as “a pattern of arbitrary arrests and detentions”, particularly concerning women activists.

The quasi-ban on protest, and restrictions around freedom of press, also seem to go against the Taliban’s initial messaging.