On December 24, 2022, the Taliban’s Ministry of Economy issued an official letter and ordered that all women employees of national and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Afghanistan stop attending work until further notice. The letter also mentioned that the ministry had recently received complaints regarding female NGO workers not adhering to the Islamic hijab and other rules and regulations imposed by the Taliban. The letter states that the ministry will cancel the licenses of the NGOs that do not comply.

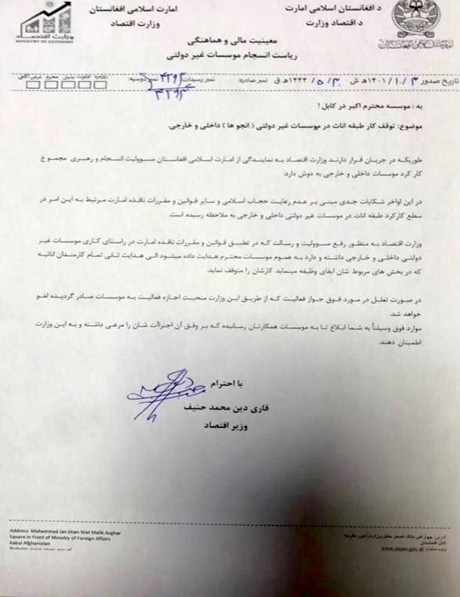

Figure: The official letter issued by the Taliban’s Ministry of Economy barring women from working with national and international NGOs in Afghanistan

The NGO ban came four days after the Taliban ordered female university students not to attend classes, and follows a series of measures stepping up restrictions on women, including blocking girls’ entrance to private education and training centres and a ban on women university lecturers, school teachers and staff from going to work. There are reports that the Taliban have also stopped women-led bakeries from operating. However, these reports could not be verified by AW investigators.

The ban on women NGO workers prompted a backlash from NGOs and aid agencies in Afghanistan, as well as efforts to engage the Taliban in dialogue. In a statement issued on December 26, 2022, the Agency Coordinating Body for Afghanistan Relief and Development (ACBAR), a network of 183 national and international NGOs whom the Taliban addressed in their letter, expressed concern over the ban and said that many of its members have stopped or reduced its activities. According to ACBAR, women form 28 per cent of the 55,249 Afghan staff of its member organisations.

On January 2, 2023, ACBAR issued another statement and said that its 183 member organisations have suspended or severely reduced their operations in the week since the ban was issued. The statement also mentioned that they had met with the Taliban’s Minister of Economy on December 29, 2022, and urged him to revoke the decision.

ACBAR member organisations, International Rescue Committee, Christian Aid, Action Aid, Norwegian Refugee Council, Save the Children, Care, World Vision, and Islamic Relief, have so far announced a full or partial suspension of their operations.

On December 31, 2022, UN Women in Afghanistan tweeted the findings of its recent survey. They reported that 86 per cent of 151 women-led or women-focused organisations have stopped or are only partially operating. According to UN Women, 38 per cent of organisations no longer work, and 48 per cent work only partially. Based on the UN Women’s estimates, the ban leaves 11.6 million women and girls in Afghanistan without vital humanitarian assistance and disrupts the livelihood of a quarter of households in the country, which are led by women.

Since the ban on women NGO workers was issued on December 24, 2022, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) has held a series of meetings with Taliban officials. On December 26, 2022, Ramiz Alakbarov, UNAMA’s Acting Head, met with Taliban Economy Minister Mohammad Hanif and called for the ban’s reversal. On January 1, 2023, Markus Potzel, UNAMA’s Acting Head, met with the Taliban’s Deputy Prime Minister Mawlavi Abdul Salam Hanafi and discussed the Taliban’s suspension of women’s access to higher education and work with NGOs. Similarly, on January 2, Potzel met with Sirajuddin Haqqani, the Taliban’s Interior Minister and on January 4, he had a meeting with َAbdul Kabir, the Taliban Political Affairs Deputy Prime Minister.

UNAMA also announced on January 4 that it will continue to pay its female staff and will not replace them with men.

Pro-Taliban social media response

Contrary to the ban on women’s higher education, which was followed by mixed reactions, the announcement of barring women from working with NGOs was almost unanimously endorsed by the pro-Taliban social media community commenting on the events, who framed NGOs as dens of immorality, westernism and espionage, and saw the loss of the female workforce as an issue easily resolved by replacing them with unemployed males.

In a “Twitter space” convened by the prominent Taliban social media activist Mobeen Khan [General Mobeen], Khan challenged a participant opposing the ban by playing on the risk of immorality, asking:

“There are 12 young men, all single, working in my NGO. Do you send your daughter, wife or sister to work in my NGO or not? I will pay her a very good salary. If I liked her age and height, and if she were beautiful, I would hire her; otherwise, not.”

A well-known Taliban social media activist, Jahid Jalal, published the official ban letter on Twitter with the following text:

“The work that should have been done long ago; Now it’s done, and it’s done well.”

Rahim Sekander, a Taliban social media activist with over one hundred thousand followers, accused NGO employees of espionage and wrote:

“The Until Further Notice is very joyful. There was a ban on women’s jobs in NGOs. The NGOs’ employees have written books and articles about their espionage job.”

Defending the decision of the Taliban, another pro-Taliban social media activist wrote about his recent experience when he went to an NGO office where half of the employees were women, but all the customers were men.

“Was there any need for women to work? Hundreds of educated men are unemployed. Why are the NGOs not employing them? But surely, under the bowl is half a bowl (there’s something fishy going on),” he tweeted.

Quoting the news about foreign ministers from 12 countries who asked the Taliban to reverse their decision, another pro-Taliban social media activist asked three questions to justify the ban, saying:

“Can’t men alone without women, who have relatively higher physical and intellectual capabilities than women, distribute aid? Secondly, without the employment of women, why do you close NGOs? What is your goal, to get women out of the house or to provide aid? Thirdly, why don’t you hire a male member of a poor family instead of a female member?”

Some video clips of pro-Taliban women on social media also defended the group’s decision. For example, in a video clip tweeted by an unofficial Taliban Twitter account, a woman with a covered face said that:

“The work of women in foreign (NGOs’) offices and organisations and their working with non-mahram men, is not allowed in Islam and is considered a great sin.”

The support for the move appears relatively organic rather than the result of a tightly coordinated campaign and likely reflects the pro-Taliban community’s long-held suspicions over the NGO sector and its close relationship with ‘the West’. While it may be a popular move, the suspension of aid work by major organisations is also likely to have a more immediate and practical impact than other recent policies targeting women, feeding discontent in areas or communities heavily supported by aid programmes.